|

How would you rate your curiosity? How often do you daydream? Is Googling an answer the same thing as satisfying a curiosity? Is curiosity innate in children or a skill that has to be taught and exercised?

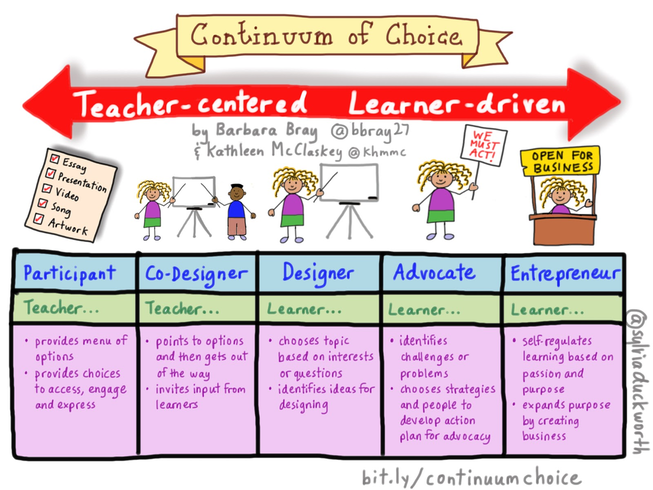

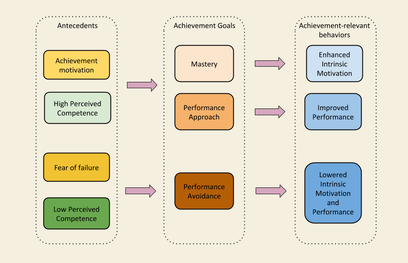

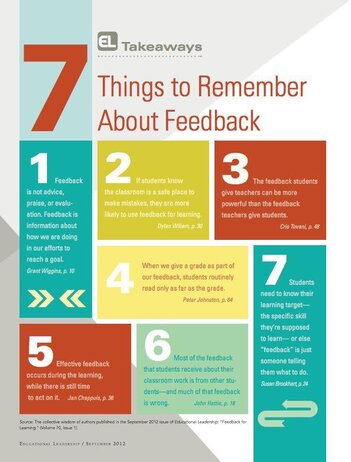

What is curiosity? We don’t have an answer from an evolutionary standpoint, except that it’s likely a side-effect of our pattern-seeking brains. You can probably imagine plenty of anecdotes where an unresolved piece of information leaves you frustrated or pensive: missing the end of an engaging movie, a text that starts with, “I need to talk to you” followed by radio silence, or an all-but-completed puzzle with one piece missing. Human brains are designed to identify and solve patterns, even inventing them where they don’t exist. Curiosity may be the haranguing inside our minds when we encounter a gap in an informational puzzle. Especially when we know that an answer does exist. When we are unsure that an answer exists, the puzzle becomes a mystery, and engages our imagination. Imagination is possibly the tinkering with that puzzle using the information we do have. Or like dreams are the organization of our recent thoughts in an aesthetic manner, curiosity and imagination could be the aesthetic loading screen of our brains transferring information from short-term to long-term memory. So where does curiosity come from? As with all education, curiosity develops best once the undergirding emotional needs are met. Curiosity competes for bandwidth in our brain against fear and anxiety, especially a fear of failure, which we have written about exhaustively in regards to school culture. A healthy environment for curiosity also requires a wide base of knowledge, which we use to make inter-connections, identify and ask questions about where the gaps in our information exist. But curiosity also requires a bit of modesty – knowing enough to know what we don’t know, but not too much that we feel certain about the information we do have. Skepticism is a friendly pairing to curiosity, and vice versa. Research has noted that households that ask questions beget curious children. It’s not simply in the act of helping with homework, reading to kids, or answering their myriad of questions, but the process of picking their young brains as well, testing the limits of their knowledge and asking them to begin considering the approach between puzzles and mysteries. Puzzles have a solution; the pleasure is the path. Mysteries may never be solved; the pleasure is in the exploration. Either way, cultivating an excitement for what you want to know first requires cultivating an appreciation for what you don’t know. Curiosity also comes from an appreciation for effort. Research shows that completing harder tasks is correlated with more engagement in that topic. This is also explained in our article about flow state and the difference between challenge and difficulty. Is curiosity under threat? Potentially. Let’s look at a 3rd grade student in a low-income setting. Last fall was their first time in a classroom since kindergarten. They had limited access to materials in order to keep pace with their virtual learning. Parents were far more likely to be working multiple jobs and/or frontline workers who were unable to work from home. There are fewer books in the home. Even a sixth grader in our class this past semester couldn’t remember a single book he’d read in the past two years. That’s not yet counting the literacy and numeracy skills they missed in the past two years. At the same time, digital consumption continues to grow. Children average ten hours of screen time per day, with low-income households averaging 1.5 hours higher per day, and growing. Thus, their interactivity with what they are consuming is becoming a one-way highway. There is little downtime or unstructured thinking time necessary to transfer information from short-term to long-term memory. At a time when information is immediately available, least reliable, and as a culture we are at the height of being uncomfortable with most forms of uncertainty. Curiosity and truth are at odds with instant gratification and superficial answers. But again, as we propose in our article about self-efficacy and game addiction, how you interact with those digital components does matter. Researcher Ian Leslie states, “The internet is making smart people smarter and dumb people dumber.” How? Googling is a useful tool, but it’s also problematically pragmatic. You don’t have to digest the question to answer it, nor do you have to digest the answer before moving onto another search query or stimulus. You don’t have to make predictions or create mind maps or engage your knowledge base of related information to make connections and deductions. For knowledge to be shifted from our short-term memory banks to long-term, we need that process to digest, settle, and organize information to grow our database and make those important links between neurons, where new bits are stored that eventually overflow and lead to breakthroughs in understanding. What are the consequences of an incurious culture? Critics argue that we don’t need long-term memory anymore because any needed information is accessible at our fingertips. That would be fine if everything we do from now on is algorithmic, but that ignores the richer, wider world of narrative thinking, of creative expression, of insight, of novel problem solving, and of emotional interactions where there are no immediate precedents or literature. It also precludes the ability to discern puzzles from mysteries, which engage our imagination, to distill what we want to know from what we don’t know, to cultivate skepticism, and to have the foundation to question those answers we so readily rely on. Go back to the third grader who can barely read and has barely read any books. We think imagination is a natural talent in children, but where would it come from? From the practice of visualizing things in their brain that aren’t really there. Where do they get that from? Books, probably. From time to sit and daydream or social pretend with other children in high-input environments with toys, games and outdoor play. If kids grow up with a greatly reduced ability to conceive of things that aren’t there, where could that lead? Besides the obvious lack of cultural, political and technological innovation, fewer works of art, fewer events of creative destruction, less insistence on replacing deprecated institutions with more modern institutions. What about a revolutionary spirit? The willingness not to accept the status quo, to imagine a different fate or future. Skepticism, critical thought. Reverse engineering what is factual and what is theoretical. Deconstructing the possibility that something that appears true, may not be. Holding in our mind both a conviction and the space for new information. Strong opinions, lightly held. Combatting our own biases; awareness of our lacking. Empathy, imagining human experiences vastly different than your own, disparate cultures, ideas, attitudes, upbringings, values, backgrounds that you’ve never thought of before. Mental health. Imagination as the ability to see a way out of depression, heartbreak, low self-esteem; to imagine what healing feels like, imagining a light at the end of the tunnel, conceiving of a different version of yourself, dreaming of who you want to be and the steps it takes to become it. Visualizing different choices than you’ve ever made before. Optimism. Having no other reason to maintain hope other than you can imagine a happy ending. So how do we get it back? One thing to pay attention to, especially in education, is how we reward and punish learning. Rewards can be just as tricky as punishments. Schools in New York and Chicago found no change in test scores when they literally offered to pay students hundreds of dollars if they got A’s on their standardized tests; yet the schools in Dallas that instead paid students for attendance and turning in homework saw marked improvements in test scores; however, Washington schools saw no change in test scores when introducing the same incentives. But did this instill any intrinsic interest in learning versus a view that learning should be compensated? A study in India found that introducing rewards too high produced lower performance. When assigning a difficult task, offering 5 months salary for completion resulted in worse performance than two weeks salary. The stakes were too high. This is why legendary athletes are scarce: they can consistently cope with those immense pressures. Punishments can also be tricky as you switch between the realms of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. A daycare in Israel grew tired of parents picking up their children late, and instituted a fine for all late-comers. This new system actually saw the number of late parents increase, theoretically because the school had then re-defined the transgression from an intrinsic moral punishment to an extrinsic economic punishment, which more people were willing to accept. The battle of extrinsic and intrinsic rewards and punishments needs a lot more research. Too much extrinsic reward undermines intrinsic motivation and dampens curiosity. Not enough can neglect a need for feedback, validation and incentives for students without a developed internal drive. Exploration and self-directed learning could go a long way. Goal-driven versus experience-driven tasks often find that students perform better over the short-term when given a defined objective, but perform better over a longer-period of time and show a greater personal interest in the subject when they are allowed to explore it without objectives attached. Meta Practice is also a new theory in neuropsychology that can be applicable. It is the idea of practicing how we practice. When it comes to developing a skill or habit, our brains have a gatekeeper that at times blocks messages being sent from our brain if it relates to an activity we associate with unpleasant feelings. This can relate to dieting, exercise, or learning a difficult subject. It also explains why reducing sugar or fatty intake and breaking addictions can be so hard: for as long we perceive the act itself, and not the aftermath, as pleasurable, our brain will regard it with positive momentum, no matter how regrettable or ill we feel after the act. Meta Practice is the idea of being more present with how we train that skill or habit that we are trying to develop or break. In the case of learning, creating a warm-up routine, a thorough but casual debriefing, and mixing in movement or mindfulness breaks can punctuate feelings of pleasure into the learning process. Autonomy and self-exploration also have higher rates of pleasure associated with them. As does carving out time for daydreaming, unstructured thought, letting ourselves dwell in the discomfort of admitting, “I don’t know. I’ll have to think about that,” and resisting the instinct to convince ourselves of an answer because it's easier than starting down a mystery.

0 Comments

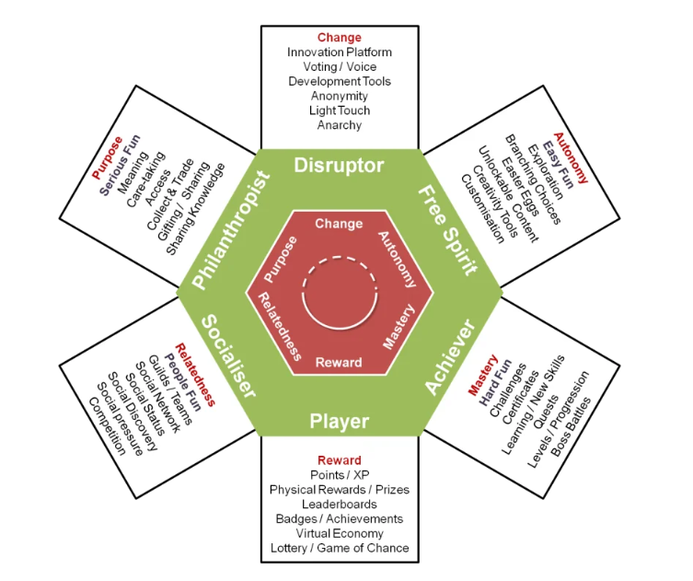

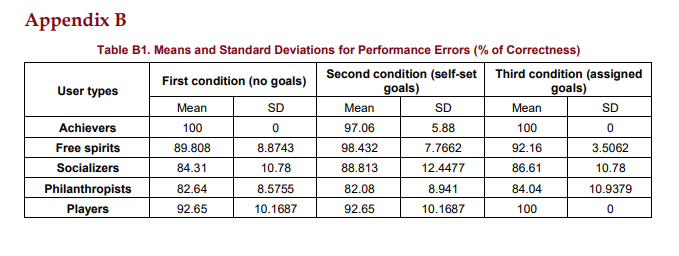

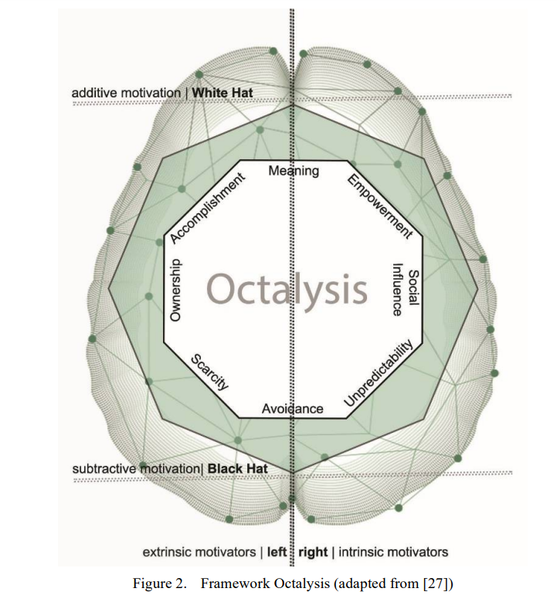

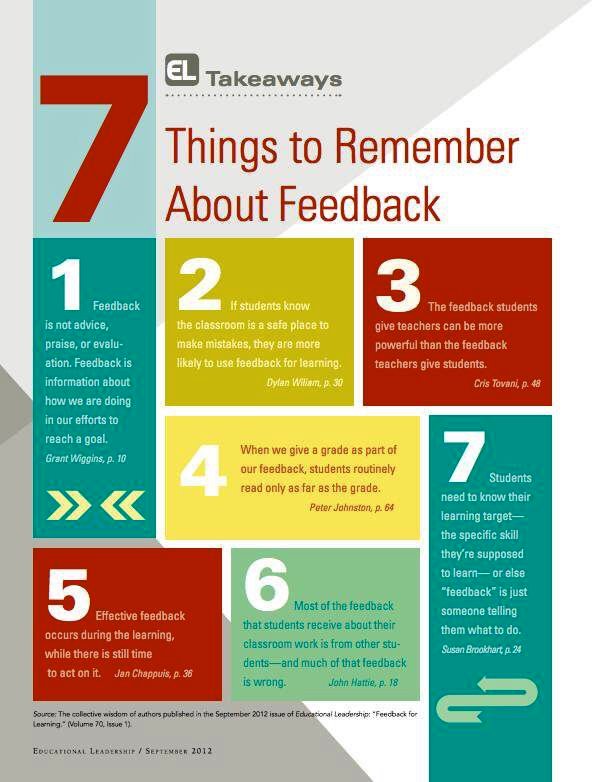

In education, one constant is the amount of assumptions that run up against a brick wall. Steven Levitt and Sendhil Mullainathan cover this topic in this podcast, distinguishing (though not defending) academics and researchers from the bulk of society who try everything they can to avoid admitting, “I don’t know.” Our most recent assumption that went up in flames was a foundational one: all kids love games. We’ve come to realize how complex of a statement this really is, and have since dived into a myriad of literature concerning Player Types (PT) and player motivations. Turns out, there are many overlaps with the previously-discussed Self-Determination Theory (SDT) framework, personality types, neuropsychology, and our beloved Agency. There a lot of different reasons why someone might enjoy playing a game, including in some cases the pleasure of ruining the game for others. This framework is useful for aligning an instructor’s approach to feedback, flexibility and engagement. We will be drawing largely on Marczewski’s Typology that studied gamification specifically, which drew on foundational research done by Bartle to produce the original Player Typology. We’ll describe what drives each PT, how they may fall to the dark side, and how one can redirect errant behaviors by understanding the underlying goals they are each seeking through their behavior. It’s important to remember, everyone is a mix of Player Types, with one type likely dominant. If you want to determine your own Player Type, you can take a quiz here. Marczewski’s HEXAD Socializers: Socializers are motivated by Relatedness, one of the tenets of SDT. Simply, they want to create social connections. They gravitate toward systems and mechanics that promote interaction, like NPCs, voting, coopetition, negotiating, and bluffing. Socializers are also perhaps the most nuanced PT, with new research citing that there are multiple subtypes that need more investigation. They are also the only type whose motivations and behaviors lie equally outside of the magic circle, interacting with and benefitting from the facilitation and organization of the real-world social setting. Philanthropists There can be a fine line between Socializers and Philanthropists, who are motivated by Purpose. Philanthropists want to feel as if they are part of something bigger, so will seek out interactive systems to achieve this, as their altruism desires to benefit other players with no expectation of personal gain. (We can recollect our moms falling into this category). Gifting, knowledge sharing, trading, community-building and sacrifice are mechanics that excite Philanthropists. This is also the type who takes the time to provide the bulk of answers on public forums, in order to help his or her gaming community. Free Spirits Free Spirits are motivated by autonomy (also part of SDT) and self-expression. They have at least two subtypes, Explorers and Creators. Explorers want as few restrictions to the width of the game as possible, and are the most likely to bump up against edge cases, find fiddly rules too restricting, propose a litany of house rules, and discover gaps in an imbalanced system. Creators want to build new things, draw and decorate their avatars, add personal content and design the world as often as possible. New research suggests a further subtyping, separating Free Spirits into those who seek Catharsis in games, or a means to escape from reality into tidier systems where they feel more freedom and efficacy; and Stimulation, or seeking excitement from the act of testing hypotheses, deduction, and assuming identities they otherwise wouldn’t have the opportunity to explore. Achievers Along with Philanthropists, Achievers are the easiest type to identify. They are motivated by mastery (or competency, as defined in SDT). They want to learn, improve, collect and seek out challenges. However, this may vary between an intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, so they may or may not brag about their accomplishments, but are likely to be hyper-competitive with themselves and possibly others in an effort to master the game. They are excited by systems that add to a game’s depth: skills, upgrades, status, and engine-building, or that add trophies and progressive feedback. Performance Taking a look at how Player Types intersect when it comes to performance during a game, we can see that, not surprisingly, Achievers dominate when it comes to no assigned goals (a feeling of competency is their main motivator) and assigned goals (winning to them is a signifier of mastery), though Achievers dip behind Free Spirits when it comes to self-assigned goals, as this is a Free Spirit’s bread and butter, and Achievers tended to choose the most difficult tasks of any type. Free Spirits performed well in each category, without specializing into mastery, and outperformed even Achievers when it came to setting their own goals, likely in the realm of creation and exploration. Since autonomy is at their core, monolithic goals like winning may actually de-incentivize them. Socializers and Philanthropists performed the most consistently, while lagging the other types in goal achievement, likely because 1) most games don’t offer purely social or philanthropic mechanics, thus limiting their ability to access their favored win conditions and 2) accomplishments and endgame status are not a primary motivator. Another interpretation is that some Socializers and Philanthropists may be naturally less competitive, or resort to social connection as a way to defer from effort, a fear of losing, or insecurity about their competency. It seems that in games, nice guys do finish last, unless they decide that success means being a nice guy. Jekyll and Hyde As mentioned previously, there are dark sides to each of the types. Some are blunt, like Griefers and Destroyers. Others, like Improvers and Influencers, can ride the line of bane or virtue. Influencers will try to change the way a system works by exerting influence over other users. In cooperative games they are known as Quarterbacks. This is not inherently negative. If they feel the system is broken and you allow them a voice to discuss changes, they can become allies and advocates. Make use of them or lose them – worse still, they could end up switching to a Griefer. Griefers (this is the Killer in Bartle’s taxonomy) are direct disruptors, in and out of the game. They want to negatively affect other users, just because they can. It may be to prove a point about the fact that they don’t like the game, don’t want to be in the learning setting, are having a bad day, or feel insecure about their competency within the game systems; or it may be that they have learned to accept negative attention as favorable to no attention. Destroyers want to break systems within the game. This may be by hacking or finding loopholes in the rules that allow them to ruin the experience for others. Their reasons again may be because they dislike the game or it may be a deviant form of exploration or mastery, hacking things or besting opponents by any means. Adding constructive feedback and scaffolding can hopefully guide them toward being an Improver. Improvers will interact with systems with the best intentions in mind. They may find loopholes or make up rules that make more sense to them, but their aim is to change the system for the better. They are similar to the Free Spirit type, in that they want the autonomy to explore the system, identify problems and fix them. With care, they can be great leaders; ignored or mistreated, and they could retreat toward a Destroyer. The trick for every PT is to identify their internal motivators and gradually convert them from being impulsively reward-seeking into setting personal goals that are harmonious with the objectives of the learning setting, if not the game. Charting a Path Toward Intrinsic Motivation We’ve spoken at length about the complexities of intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation, and how games are superb at reinforcing self-efficacy. But as an instructor, part of the job is to make students aware of their own motivators and give them the tools to create their own sense of engagement. One simple source is empowerment. People tend not to enjoy things they’re bad at. Playing to a student’s strengths can make the difference between their light and dark sides, even if it means skewing systems to benefit the way in which a struggling student wants to play the game. Asymmetrical games or contrived asymmetry (tacitly giving one student improved abilities or equipment) can make players feel special, empowered, or give them the proper scaffolding to compete with more advanced players. Another source of engagement is meaning. We mentioned asymmetry, but another facet of balance is that players need to feel that their choices have influence over their outcome in the game. This is called self-efficacy or meaning-making. It’s what connects players to the magic circle, their avatar, the narrative arc and the social dynamics of a group. If it’s not apparent, accessible and rewarding within the game, Griefers and Destroyers can often spot an easy path to self-efficacy by ruining the game for others. Some methods to improve meaning don’t even have to be inside the game. Assigning one player as a Captain or Leader, a Rule’s Sherriff, a Treasurer, a Cartographer, etc. can give them a sense of purpose and value, as well as incentivize them to become a role model or abide by the game’s rules to maintain their status. Jobs can apply in the game as well, using roles that would apply to a mission, phase or achievement in the game. Counter-intuitively, cooperative games aren’t always the best choice for game-based learning (until you know your players well and have established mutual trust). This is because Griefers and Destroyers can wreak havoc on a cooperative game. In competitive games, at least the game’s systems can fulfill some of their negative intentions. But if everyone’s fun is hinged on them agreeing to play cooperatively, they may see this as an easy opportunity to wield their displeasure over the rest of the group. Splitting the players into competing teams may give disruptors a sense of allegiance and relatedness, as well as lowering the stakes so that they don’t feel as if they are solely responsible for their failure. It’s also a good idea to start off gaming sessions by reminding students that there is no penalty for losing or making bad decisions. Everyone is going to make mistakes; the point of games is iteration. School has given most students a phobia of failure. Try to undo that a bit at a time by lowering the consequences of experimentation – who says you even need to keep track of score accurately? Or consider supplementing scoring with individual inspiration points, meta currency or rewards toward a mega game. Physical rewards work wonders. Kids love nothing more than possessing something. Creating real-world trinkets, drawings, maps, figurines, cards, treasures and souvenirs that bring the game to life spark so much joy, and give them a tangible and emotional connection to positive outcomes. This is a perfect example showing that the best form of teaching is creating experiences. Combined with upgrades, skills, unlocks, discoveries, etc. these all provide demonstrable evidence of progress. Progress = competency = empowerment = engagement = curiosity = discovery = repeat. One thing to keep in mind: rewards, empowerment, and meaning should all be focused around the core loop of the system you are trying to teach. The act of a student demonstrating comprehension of a core learning objective should ALWAYS result in a pleasurable experience. That’s what games are most beautiful at: attaching intense, memorable, visceral feelings to great choices. For specific Player Types, let’s take a look at additive vs. subtractive motivators, and left brain (logic and analyzation) vs. right brain (creativity and socialization) motivators. For Free Spirits, Socializers, Improvers and Influencers, try to offer them less regulation and let them discover their own paths and rules. They thrive on anticipation, not results. Feed them unpredictable game states, randomness, social influence, an amplified voice, and opportunities for teamwork or treachery.

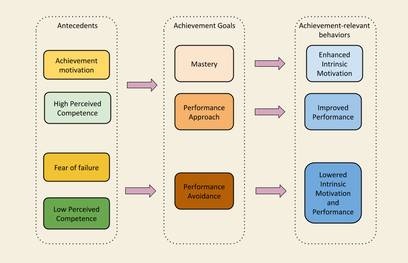

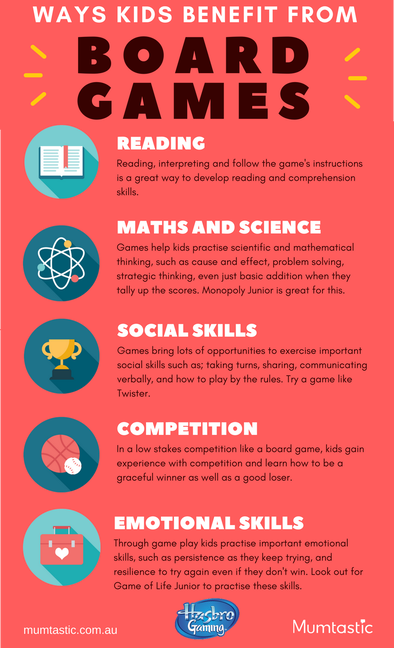

With Achievers, Griefers, and Destroyers, make them feel special. Scarcity, tasks, and personalization can be one way to help them appreciate a personal goal or reward. Invent trophies, rare items they can possess, and special missions. Just as in real-world economics, something is far more valuable when it is one-of-a-kind. As a post-mortem of this article, a colleague asked if this analysis applied to non-gamified learning, as well as adult learners. We can assume that most elements can be applied to any interactive learning setting, and any stage of development. Though separate research tells us that older learners gain more from repetition, whereas younger learners gain more from social proximity and the quality of direct and immediate feedback. Anecdotally, many of us can probably safely classify our moms as Philanthropists during childhood games. As for how well this typology extends to other realms of learning, we say: be the experiment you want to see in the world. In the gaming industry, there is no shortage of definitions for “game” or “play.” This article isn’t overly concerned with the what, as much as asking why we play, and the various ways in which we’ve studied how we play. There is also no shortage of the studies of play. The American Psychological Association found that children who engaged in active play for 1 hour per day were better able to think creatively and multitask. Gamers also exhibited more emotional resilience during conflicts. Columbia University showed that physical play in 7- to 9-year-olds enhanced attentional inhibition (patience, focus and organization) and cognitive flexibility (the ability to grasp concepts more quickly as well as make connections and switch between concepts). As for why we play: essentially, play is practice. Given that play can be as abstracted, imaginative and social as we desire, play can better prepare us for nearly every realm of life. What gives play that power is the intention of meaningful discovery in a safe environment through the process of trial and error. The greatest benefit to play might be its attitude toward failure. So if play is inseparable from failure, and education is inseparable from play, shouldn’t failure be inseparable from education? Our experience tells us that students are far more likely to view failure as inseparable from finality. Meaningful Discovery The field of play is a field of discovery, and also catharsis. Rough, sporting, and competitive play enables people to safely explore multiple boundaries within the parameters of a game. Consequences are temporary. There is research linking the cessation of sporting activities during the pandemic with a rise in violence. Healthy conflict fosters communication, negotiation, fairness, and emotional regulation. It also stokes a curiosity for risk-taking (one of our Guiding Principles) while developing empathy as young minds learn the dual nature of harm. Another benefit it that play supports mental visualization. Make-believe. Through a series of experiments, researchers showed that students in small groups who explored a new concept before a lecture measured stronger comprehension than those who experienced the lecture before self-exploration. This has been reproduced in pre-schoolers better enumerating uses for an object pre vs. post instruction. Because they encountered more Productive Failure, thus iteration, students who began their learning without direct intervention developed more semantic knowledge and transference. Learning through play establishes personal connections of how and when to apply new concepts. Scaffolding Conversely, guided play, also called scaffolding, has supporting research as well. A famous researcher in the education world, Vygotsky, theorized that the most efficient learning occurs when a teacher is present to scaffold content in a way that resonates with and builds on top of a student’s prior experiences. Cambridge University used this concept in game-based learning to find that centering play around a defined goal, while allowing children to try various paths toward reaching that goal, did benefit their comprehension better than either self-exploration or direct instruction. For many of us, a “serve-and-return” form of play does begin from birth and follows us through much of our adolescence. Consider how much nonverbal communication and interaction transpires before a child learns to speak. Smiling, laughing, cooing, fear, discomfort and doubt can all lead to a reciprocal dance between child and parent. Social and Role Play Sociodramatic play is when children act out the roles of adulthood from having observed the behavior of adults. Studies suggest that this function of play is to build a prosocial brain that mimics effective peer interactions. Rats that were deprived of play as pups not only were less competent at navigating mazes later on, but their medial pre-frontal cortex was significantly less mature, suggesting that play deprivation actually stunts physical brain development. Rats with reduced access to play acted less socially and communally when they encountered other rats later in life. The concept of development and maturity is especially important, as some of the health effects of social play can’t be seen in the immediate or even medium term. A Berkeley study found that third-grade prosocial interaction correlated with those students’ eighth-grade reading and math outcomes better than with their third-grade reading and math outcomes. Fun: It Keeps You From Being a Grumpy Jerk Play and stress are also closely linked. Higher amounts of play are associated with lower levels of cortisol (stress chemicals). Play also activates norepinephrine, which facilitates synaptic connections and improves brain plasticity. The maturing of the pre-frontal cortex, as shown previously in lab rats, moderates the impulsiveness, emotionality, and aggression of the amygdala. Let’s translate all that. Taken place in a safe environment, play lowers stress, stimulates chemicals that help the brain learn, and during times of conflict and adversity provides a template for resilience, judgment and maturity against our primal impulses. Theoretically, play may be an effective therapy to an overactive amygdala, aggression, and uncontrolled emotions that result from childhood adversity, stress and trauma. This is likely why role play can be such a useful tool for developing empathy. To Screen or Not to Screen? Now that we’ve established so much goodness around play, a secondary topic emerges: video games versus in-person games. The bulk of studies in the gaming world center around video games, due to the fact that video game companies can and do pour a lot of money into research to defend and extol the benefits of gaming. Many reliable studies have found that video game players do show higher intellectual functioning, higher academic achievement, better peer relationships, and fewer mental health difficulties than non-gamers – though at this point, upwards of 75% of the population may fall into the casual gaming category. Parsing out the difference in quality between types of gaming is harder. One Berkeley study did compare traditional and digital toys, and found that traditional toys were associated with an increased quality and quantity of language development compared with electronic toys, particularly against solo electronic toys. In social pretend play, without the aid of a digital setting, children must collaborate on an environment and assign roles, which improves their ability to reason about hypothetical events. Digital media, if supported by scaffolding or co-play with peers, may have similar benefits, though the thinnest barrier between human-to-human interaction likely remains the best environment for learning. As humans are naturally communal, combinatorial innovation is far more likely to occur and spread through physical proximity. Good Failing and Bad Failing We spoke previously about the idea of Productive Failure and how it stoked creativity, problem solving and comprehension. The caveat to those findings is crucial: the consequences of failure cannot be perceived as too great, i.e. how most every student in the public education system perceives failing. Instead of creating an atmosphere where failure means trial and error, iteration, semantic connections and growth, failure has become a looming threat. This leads to performance avoidance, where instead of pursuing knowledge for its applications, interests or value, students perform only as well as sees them avoid punishment. They may never achieve a path to intrinsic motivation or independent learning, and may always rely on external incentives. In the world of game design, the only time a designer implements a system that subtracts is to introduce tension to the player experience. A timer counting down, running out of ammo, or losing all your money. This is the experience students encounter at school five days a week.

The value of grades and test scores holds their agency (another Guiding Principle) hostage. Supposedly, Google allows engineers to spend 20% of their office time on any project they desire, whether or not it’s related to work (though undoubtedly Google has a right to anything that is produced). As a result, productivity and retention are high, while upwards of 50% of their commercial projects come from employees pursuing an outside interest. Some schools have adopted this system by letting students study interests and hobbies unrelated to curriculum. Turning education back into play. They have shown reduced drop-out rates, improved behavior, boosted grades, and increased motivation. We are very interested in asking those students the original question, “How important is failure?” Learning Setting (SEL) There’s a notable study where preschoolers were instructed to wait alone in a room with a piece of candy, and promised a second piece of candy if they chose not to eat the first until the proctor returned. The preschoolers with the self-control to wait for the larger reward showed higher academic performance throughout adolescence. Pretty unremarkable stuff. Recently, a preface study was added to this experiment. Before the candy phase, the children waited in the room with drawing paper and a box of broken crayons. The proctor promised to bring each child a new box of crayons, but only half the children ever received one. Advancing to the candy phase, the preschoolers who had not received the promised crayons were 5 times more likely to eat the first piece of candy than children whose crayon promise had been fulfilled. Pretty powerful stuff.

A deficit of trust is the daily experience of an enormous number of students. Academics aside, this has huge implications on their mental health, as we see a rise in suicides, anxiety levels and mental health disorders in children aged 8-15. One colleague put it best when he said that the average student is in a constant state of “coping.” Learning Outcomes (FTW) Academics to the fore, let’s connect learning setting with student performance; specifically, how it filters into two types of goal achievement. One is performance-approach, meaning the individual has an intrinsic stake in a process and its reward. The second is performance-avoidance, where a lack of confidence or a fear of failure drives a singular goal of avoiding punishment or penalty. They are both positive feedback loops. They feed into themselves. As observed, a child’s learning path can be lost far younger and more easily than you’d expect. Combined with a system of social comparison (grades), high performers increase their advantage and self-efficacy, while low performers lose agency and self-efficacy as they further identify as failures. A positive self-efficacy continually improves a student’s belief in their effort and abilities. They have confidence that they can achieve a result if they put in the work, as well as determine which rewards are worth the effort. They can negotiate value and design goals that are personally meaningful to them. Students empowered with positive self-efficacy can observe skills modeled in the world and have the intrinsic drive to learn and apply them to challenging problem sets. They are curious, entrepreneurial, pro-active and independent. They start asking questions instead of simply answering them. They become lifelong learners. Avoidant students experience heightened levels of anxiety and stress. Their motivation is driven by the desire to achieve the bare minimum and escape punishment. They feel their choices and effort are meaningless. Failure in a monolithic system gives a student nowhere else to go. This is what many kids cope with. “I can’t do this. None of my choices matter. My effort doesn’t matter. I have nowhere else to go.” That is a chilling narrative to tell one’s self day in, day out. Where Games Come In (GBL) Given the elasticity and sensitivity of young brains, think about how impactful it is to encounter a scoring system which removes points, versus one that earns points. Separate research confirms that having something taken away affects brain chemistry 3 times more intensely than gaining something. Additive scoring creates a far healthier learning environment than punitive scoring. Is it any wonder why games provide an escape for so many kids? (Jane McGonigal does wonderful research on games for positive social and emotional change. She buckets the antecedents as “Everything sucks, I’m gonna play games instead,” and “My life is better when I am able to include games.”) Games provide a natural system of scaffolding, the process of introducing a skill, iterating on it, observing and rewarding measurable improvement, encountering a task-oriented trial and graduating to mastery. This is called Flow, a balance of increasing challenge in proportion to skill to create a state of hyper concentration and absorption. You might see a gamer in Flow and think they are zombified. In truth, their brain is experiencing the pinnacle of all learning and performance environments. Where games succeed is in understanding that failure cannot be binary; failure should be an indicator that you need to try something different, not that you can’t do it. Secondly, an individual needs the freedom to choose their own path toward solving problems. Thirdly, the individual must see the value of the reward as worth the effort. Games, games, games.

So is gaming an escape, or is it a cry for self-efficacy?

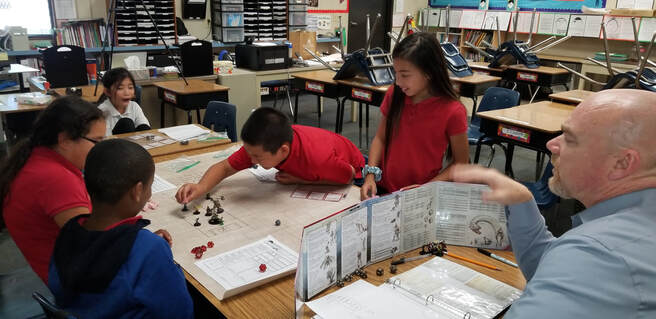

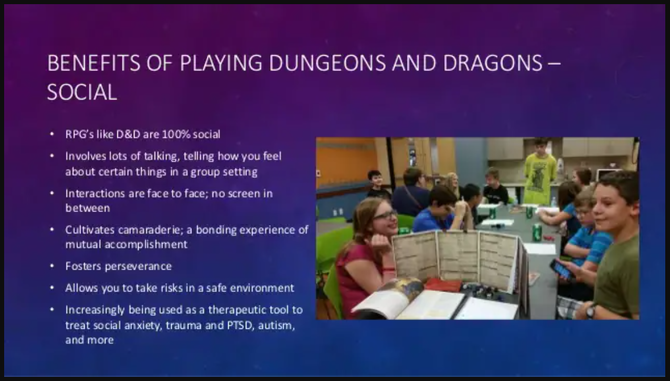

As we defined in our last post our assertion that school is a poorly-designed game, today we’ll compare the education system to a well-designed game, Dungeons & Dragons, and how we’ve seen students respond in the 5 years of using similar RPGs in the classroom. If you think the same quantifiable progress can’t be made through games, remember that games are almost purely made out of both quantifiable systems and systems of progress. Our students’ reading test scores improved dramatically, specifically their ability to identify relevant information from a passage. This comes from scouring a rulebook for specific information about their character, feats, weapons, rules, etc. Their ability to chunk texts and recreate a narrative in their own words improved as well. This was due to their interaction with so many nuanced characters and plot cues, foreshadowing, and having to make inferences about the game's story based on subtle clues and conversations. Basic math skills improved, including probability and deductive reasoning, less to do with equations and more to do with comparisons and decision-making. Also embedded in game math is a basic understanding of economics, value versus worth, resource management and distribution. Social problem solving increased. We wrote in the last article how failure is abstracted in schools. In narrative RPGs, problems are abstracted but failure is clearly defined, though not finite. Players immediately knew what they did wrong, which approach didn’t work, and became less afraid to make mistakes, since mistakes weren’t punitive. They result in a denial of progress, but nothing is lost. Mistakes require iteration. There is no penalty for solving a problem incorrectly, either once or ten times. Because of this students were introduced to the concept of alternating skills to find the one that worked best per situation. This also promoted cooperation between students. Their negotiation of strengths and weaknesses within the group was a refreshing departure from their binary labels of "high” or “low" students. As their individual character strengths grew, each student became identified by those strengths and depended on teammates to make up for their weaknesses. Another theory for their advancement with social problem solving is that the visibility and stressors of their normal lives and of the real world were absent in the game, or metaphorical, removing some of the intimidation in trying to solve them. Jamie Madigan, on The Psychology of Video Games, has a great episode about a group of therapists who use D&D with their patients by creating campaign scenarios relevant to the patients’ real world struggles, but abstracted in a safer game environment. In what eventually became the impetus for founding UnboxEd, in our 5th year we first experimented with using D&D to start a business with our students. Having economics and investing backgrounds, we made sure that the kids didn't get away with anything they didn't earn. Using the D20 System, modified character stats and our own experiences in commerce, we built a weekly P&L statement that covered payroll, property and corporate taxes, third party consultants, talent recruitment, supply chains, employee equity, ticket sales, concessions, promotions, marketing, litigation and on and on.

Halfway through the campaign, the growth of the business depended on the kids figuring out a way to invent the radio. The biggest challenge was how to power the device with no electricity existing within the world. One of the students in the group was in danger of failing fifth grade, and was in the at-risk category of dropping out before graduating high school. But he had an idea. For an entire year, he chose to stay an hour after school, twice a week, to attend college within our game, to learn chemical and electrical engineering, so he could invent a magical battery to power our radio. He ended up passing 5th grade. We were lucky enough to reconnect with those students recently, and he’s on track to graduate high school. We asked him during that year if he wanted to be an engineer in real life. He said, "No. I’m not one of the smart kids." Hating school doesn't mean hating learning any more than hating dodgeball means hating sports. I fail to see how his achievement in the game was different than a real-life outcome. It took discipline, persistence, luck, guidance, and time. The real difference is that the school he went to in the game was the version of learning that he wanted to see. The version he agreed to. Instead of an evaluation system that told him over and over that he wasn’t capable of what other kids were, he started with nothing and began to climb. He made all of the choices himself, and he recognized all of the obstacles ahead of him, that there were no guarantees, and while there were plenty of efforts that didn’t work, there was nothing in the system that told him he couldn’t succeed. There are plenty of rumors surrounding why our educational system is designed the way that it is, plenty of conflicting ideas on how to fix it, and plenty of past solutions that are now part of the blame for its current quagmire. Strangely enough, when UnboxEd was in development and we began to compare our ideals with the design of public schools, we realized that our educational system can actually fall under the definition of a game.

Let’s elaborate on each. Beyond the simplest function of making a game "work," what do rules serve? Rules shape the interactivity of elements in a game world. We often find stricter rule sets in linear games (players progress on a single ‘golden’ path, with transparent goals), while open, explorative games allow players more agency in their interaction, often using the player’s biases and assumptions as part of the puzzle that they must overcome. School falls under the linear, narrow campaign. Little, if any, of its systems are designed to respond to student agency. Rather, success often depends on students who are built for its demands. It’s a shame that we’ve gotten to a point, with a concept like education that we consider so exploratory, that not even the educators themselves have control or consent over the systems of education. So what is lost in that model? Being part of the rules process means you are invested in the system as a stakeholder and constituent. You have ownership over your world, and feel responsibility to abide by the rules you helped create. Skin in the game creates an incentive to preserve its integrity. Scoring, however, is our biggest gripe with public education. Grades cap achievement at 100, and count down commensurate with a student's errors. As a game designer, the only time we include a mechanism which counts down, be it a timer or health gauge, is when our aim is to introduce tension and pressure to the player experience. That's what grades do to students. This scoring system evaluates a narrow set of skills, mainly raw intelligence and memory, with some compensation for work ethic. It also ensures that all students are directly compared to one another on these few, specific skills without taking into account character or creativity. Students are labeled as "high performing", "low performing", or "average". They carry this mono-identity with them throughout their learning universe. They have no choice but to internalize it. "I am a [performance status] student". This system does not measure growth, it measures decay. Take a well-designed game as a comparator. Dungeons & Dragons begins every character at level zero and counts up as they progress, to a limitless number. Notice a difference in the language itself. You “gain” levels, “increase” experience points, “acquire” abilities, skills, feats, currency, and items. Failure is not punitive: it simply shifts the problem to a different set of trials. If A didn’t work, you try B. Players recognize the freedom to experiment with various paths, which incentivizes and rewards imagination and iteration. Each character has a unique path to achieving unique goals, solutions and growth. Instead of comparing one’s self to another student’s abilities and achievements, each student can identify as an inclusive sum of both strengths and weaknesses. Through the game universe, players constantly call, "I’m good at [ability], but I can't [skill] yet." Answered with, "No problem, I’ve got [skill]. Can anyone [ability]?" Think of game states as phases, arrived at through current factors and conditions. I want to focus on the Fail State. There is one major problem with the Fail State at school. It is binary and therefore abstracted from a goal as broad as cognitive growth. Pass or Fail. Those are the options. Which means students are not attempting to learn the material, they are attempting to achieve a Passing State. There's a big difference.

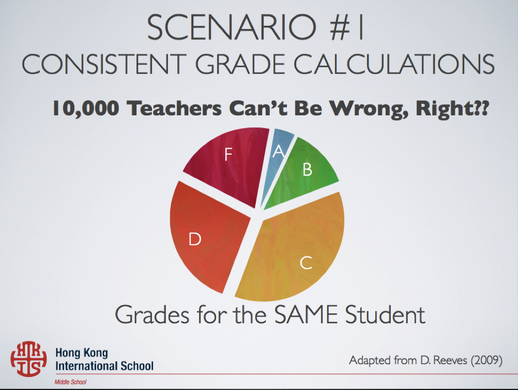

Without any nuance beyond Pass or Fail, students often don't care what they achieved, only IF they achieved the desired state. As educators, we consider the student having mastered or not mastered the material, mark the grade and move on to the next unit. The machine grinds on. Students don't experience a consequence until the next time a cumulative concept builds on top of the previously unmastered material, and they fall farther behind. If a student were to guess at each exam without understanding the material and luckily scored excellent grades, they would absolutely consider that a success. But would a parent or teacher consider that a success? Then who are our students learning for? Grades have been divorced from the premise of learning. The Pass/Fail State in school reduces achievement to a reactive, quantifiable chore, versus what could be a rich, meaningful action that demonstrates achievement. The current design teaches students to care more about achieving a high score than about learning, which makes cheating a profitable and sometimes smartest choice, under the lens of optimizing the game we've put in from of them. Good designers don’t blame players for breaking their game. They consider it poor design and fix it. This Spring, we were honored to appear on the Mat & Board podcast to talk about our work using Narrative RPGs in the classroom. The episode features a conversation about the background of the program, the democratization of rules, evaluation and feedback systems, and games as powerful simulators.

We also caught the attention of Wizards of the Coast (makers of D&D) who interviewed us in their official D&D Magazine! Hope you enjoy. |

SubscribeSign up to receive monthly emails, sharing research and insights into the world of game-based learning. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed