|

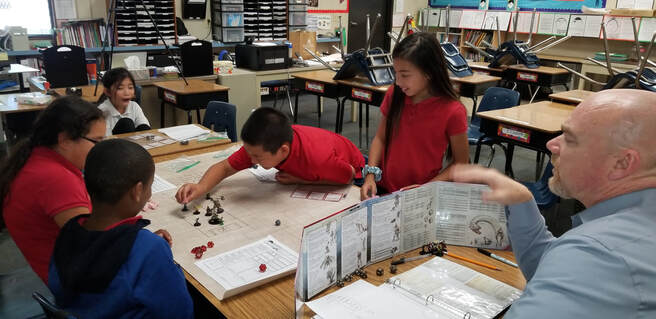

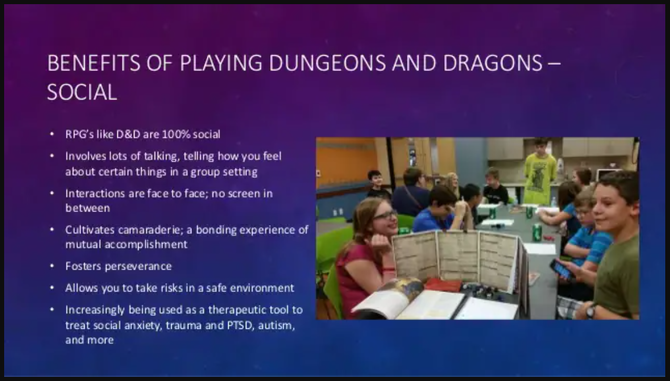

As we defined in our last post our assertion that school is a poorly-designed game, today we’ll compare the education system to a well-designed game, Dungeons & Dragons, and how we’ve seen students respond in the 5 years of using similar RPGs in the classroom. If you think the same quantifiable progress can’t be made through games, remember that games are almost purely made out of both quantifiable systems and systems of progress. Our students’ reading test scores improved dramatically, specifically their ability to identify relevant information from a passage. This comes from scouring a rulebook for specific information about their character, feats, weapons, rules, etc. Their ability to chunk texts and recreate a narrative in their own words improved as well. This was due to their interaction with so many nuanced characters and plot cues, foreshadowing, and having to make inferences about the game's story based on subtle clues and conversations. Basic math skills improved, including probability and deductive reasoning, less to do with equations and more to do with comparisons and decision-making. Also embedded in game math is a basic understanding of economics, value versus worth, resource management and distribution. Social problem solving increased. We wrote in the last article how failure is abstracted in schools. In narrative RPGs, problems are abstracted but failure is clearly defined, though not finite. Players immediately knew what they did wrong, which approach didn’t work, and became less afraid to make mistakes, since mistakes weren’t punitive. They result in a denial of progress, but nothing is lost. Mistakes require iteration. There is no penalty for solving a problem incorrectly, either once or ten times. Because of this students were introduced to the concept of alternating skills to find the one that worked best per situation. This also promoted cooperation between students. Their negotiation of strengths and weaknesses within the group was a refreshing departure from their binary labels of "high” or “low" students. As their individual character strengths grew, each student became identified by those strengths and depended on teammates to make up for their weaknesses. Another theory for their advancement with social problem solving is that the visibility and stressors of their normal lives and of the real world were absent in the game, or metaphorical, removing some of the intimidation in trying to solve them. Jamie Madigan, on The Psychology of Video Games, has a great episode about a group of therapists who use D&D with their patients by creating campaign scenarios relevant to the patients’ real world struggles, but abstracted in a safer game environment. In what eventually became the impetus for founding UnboxEd, in our 5th year we first experimented with using D&D to start a business with our students. Having economics and investing backgrounds, we made sure that the kids didn't get away with anything they didn't earn. Using the D20 System, modified character stats and our own experiences in commerce, we built a weekly P&L statement that covered payroll, property and corporate taxes, third party consultants, talent recruitment, supply chains, employee equity, ticket sales, concessions, promotions, marketing, litigation and on and on.

Halfway through the campaign, the growth of the business depended on the kids figuring out a way to invent the radio. The biggest challenge was how to power the device with no electricity existing within the world. One of the students in the group was in danger of failing fifth grade, and was in the at-risk category of dropping out before graduating high school. But he had an idea. For an entire year, he chose to stay an hour after school, twice a week, to attend college within our game, to learn chemical and electrical engineering, so he could invent a magical battery to power our radio. He ended up passing 5th grade. We were lucky enough to reconnect with those students recently, and he’s on track to graduate high school. We asked him during that year if he wanted to be an engineer in real life. He said, "No. I’m not one of the smart kids." Hating school doesn't mean hating learning any more than hating dodgeball means hating sports. I fail to see how his achievement in the game was different than a real-life outcome. It took discipline, persistence, luck, guidance, and time. The real difference is that the school he went to in the game was the version of learning that he wanted to see. The version he agreed to. Instead of an evaluation system that told him over and over that he wasn’t capable of what other kids were, he started with nothing and began to climb. He made all of the choices himself, and he recognized all of the obstacles ahead of him, that there were no guarantees, and while there were plenty of efforts that didn’t work, there was nothing in the system that told him he couldn’t succeed.

0 Comments

|

SubscribeSign up to receive monthly emails, sharing research and insights into the world of game-based learning. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed