|

I recently asked a friend of mine, during a career transition, what his dream job was. He considered it for a long time, as if he had never thought about it before. Almost as if he was trying to imagine a different version of himself who had the freedom to pursue a career based on his passions. He ended up answering with something practical, profitable, and not far off of his current career path. I reframed the question to ask, “If you went back in time to re-do college, what would you study?” It’s a question I enjoy daydreaming about and asking new acquaintances. Personally, I imagine studying architecture or food science. Every time I see chocolate being made I feel an artisanal pang to do it, as does the prospect of being a flavor meister at Jelly Belly. This month I wanted to ditch the royal "we," data and supplemental media (mostly) and write something personal, about passion. After taking a break from social media and blog articles in August, due to a lot of activity with contracts and curriculum for the new semester, vendor fairs and expos, and our first round of hiring instructors, I came to the point of having to accept how many hats I can sustainably wear. In the past month, the topic of passion has resurfaced over and over again. As someone who just started designing their dream job in middle-age, I wanted to share aspects of my own journey with passion, the founding of a nonprofit, and the educational community. To my comfort, I learned that middle-age is the best time to become an entrepreneur. Media and the celebrity of college-dropouts-come-tech-titans have given us this impression that entrepreneurship is a young person’s game. But consider it. I spend a lot of time around youth, and one thing that stands out right away is that they’re pretty bad at most stuff. Contrast that to someone with 20 years of experience in an industry, who knows its needs and gaps, has their ducks in a row, and has experienced enough failure to know that failure is a part of the process. For this reason, the vast majority of successful entrepreneurs happen to be middle-aged. As it happens, I have a half-dozen middle-aged friends starting various business as well. I’ve started a resource group to support each other, which we call Dreamers & Schemers. We talk frequently about feeling overwhelmed at times, and doubtful. But those have both been the exception to the experience of waking up most mornings with enthusiasm and heartfire. As another symptom of middle age, I have a good handle on my discipline and boundaries. I work an 8 – 5 exclusively. That includes gym and errands. Occasionally work creeps up to 5:30, but only because I’m in a flow state and enjoying what I’m working on. I find it easy to follow my interests and instinct, and draw a line between work and life. And I have a wonderful wife and friends who provide enormous support. August also marked our anniversary as a company. In that year I’ve transitioned from dreading and doubting my decision to form UnboxEd as a nonprofit to now defending and counseling people who are nervous about embarking on the nonprofit route. The simplest thing I can say is that the first year has been way simpler than I anticipated. That may not be true for the coming years, but I feel more than prepared for what they bring on the nonprofit front. And I’m happy to share resources and guidance separately. Chasing one’s passion not only seems scarce in the professional setting, but it’s needed now more than ever. Despite the uptick in business creation during the pandemic, small business starts have been declining for decades. This has a huge impact on worker satisfaction, wage gaps, pricing power of companies, and more importantly to me, community cohesion and reinvestment. One thing I admire about Austin is its culture on sustaining and valuing local businesses. I firmly believe that practical jobs are going to disappear to automation and AI faster than we realize. Which makes me think that most people will have less and less to lose through chasing a passion, and starting early, often and less unequipped than they’d like; all the while society will need more and more passionate people doing creative things that automation cannot replace and that invite people into a human, purposeful community. Unemployment is correlated with a lack of attendance at religious and social events. People tend to withdraw when they don’t feel as if they are contributing to society. I believe that is a problem we will need to address relatively soon, on a surprising scale. The People I Mostly Admire is a valuable podcast for hearing from successful people who have chased their passion and where it led them. Andrew Yang’s interview talks specifically about the dire need for passionate creators. I mentioned failure earlier, as a distinction between youth and maturity. It’s maybe more of a double-edge sword than I considered. One on hand, as we go through life, failure becomes more practiced, as does wisdom in response to it. Yet there is one looming fear that entrepreneurs take on, I think, which is the danger of identifying with failure. “If this thing fails, if I give it my best and it isn’t good enough, there will be no one else to blame, no other excuse except my inadequacy. What does that say about me? Am I good enough? What next? I won’t even have a dream job to fantasize about.” Yeah, I don’t know. I haven’t conquered that fear yet. It still grips me from time to time. Especially, ironically, when things are going well. When there’s so much on my plate and it all falls to me. Some days I think, “I could quit now, call it a moderate success, keep it in my pocket and go back to something more streamlined, anonymous and flexible.” Maybe that fear will always be there. Beats me. If you find any good advice for this one, let me know. But small victories, and gratitude. Those are instrumental. I bought a new printer and office chair this week while I waited on a vital contract that was 15 days-and-counting delayed. I am very excited about those additions to our team. The next time I need a boost, I’m going to let myself daydream about buying a sweet paper cutter, too. The last article we published, focusing on Literacy, dealt with a lot of these themes: identifying one’s heartfire, visualizing that it is achievable for this version of you in this reality, what it takes to chase it, and how to develop each of those tools. It’s lofty and ambitious, but that is truly our mission. When I think of students, I do not think of college and jobs and global problems. Community and citizenry and creativity is inseparable to me from their and our future. Leaving room for what we haven’t the context to envision. But that’s our journey. That’s where we’re at, where I’m at. As ever, and also part of our mission, what doesn’t sound better as a story? To speak about life’s cycles and kismet and validation and gratitude, let me introduce you to Felix. Felix was one of our first hires that we made this semester. He’ll be joining me in our Social-Emotional Storytelling class. I happened to meet Felix when he was 9 or 10. He’s 20-something now. He was a student in my first-ever afterschool D&D club, over a decade ago. A few months ago he found me on LinkedIn via an article I wrote about D&D in the classroom. He reached out, informed me that he and 4 or 5 other former students still played D&D weekly, and invited me to join a game. I jumped at the chance, enjoyed an at-times awkward but mostly amazing reunion with my old students, and proceeded to mercilessly derail Felix’s 5-hour campaign as the sort of payback that all teachers dream of. Yet, the initiative, the experience, the passion, left such an impression on me that the following week, when I needed to hire two new instructors for the program, he was the first person I called. Welcome to UnboxEd, Felix. Here is a short interview to introduce you to his own journey: Felix, Professional Game Master/Instructor Stefan: Describe your dream job.

Felix: For the longest time I believed my creative dreams, whether it be doctor or astronaut or inventor, were unobtainable. In other words, I viewed them as things that only happened to people in movies. Today, I'm asked a question I used to find terribly difficult to answer, and I face it with confidence. I WANT TO BE A WRITER. (The capital letters indicate that I’m shouting it from the rooftops.) Regularly, I would have just said author, but I feel like I want my creative agency to span into multiple categories. Whether it be Dungeons & Dragons, or screenplays or novels. I believe that it is my goal to create a story that will make whomever interacts with it feel every emotion, and I believe that I have the skills to do it. Stefan: Lame. (Just kidding.) Speaking of D&D, what benefits from D&D and RPGs in general have you seen in your life? Felix: Lots of English teachers over the years would tell me how wildly creative I was; I had a significant amount of family members that wrote professionally, and much more. But the one memory I tie closest to when my brain switched and told me that every job (specifically creative jobs) were obtainable to me, was when my elementary Dungeons & Dragons teacher allowed me to run a campaign. It was horrible, absolutely awful. Some of the worst written stuff I've ever seen. I'm pretty sure it was based off of a video game, and it didn't make any sense. But I loved every second of it. I cherish that memory despite wanting to permanently erase it from my mind due to how embarrassing it was. Something about that moment of having agency over a creative project really took over in my mind. I would scribble short stories in my notebook every day. Once that moment had happened, I started caring so much more about the games we played. I started to realize that even when I was a player I was still creating and telling my own story. I feel like D&D is the biggest reason I got back into writing books. I had given up for so long because I felt once again that it was too far of a dream to achieve, but running a roleplaying game gave me the halfway point between playing games and writing a novel. I realized it didn't feel difficult to write and I started writing again in both mediums. Stefan: Everyone’s going to think I coached you to say that. So now you’re back, on the other side of the table. Why? What do you hope to accomplish as an instructor? Felix: To ensure that everyone is having fun, and that at the end of the campaign, there are memorable story moments that every player will remember. You have to recognize that the story is not entirely focused on you alone, and that if you make it that way, the people around you won't have fun. It is also your job to make sure that your fellow players are feeling comfortable. If they feel like they can't speak up, or feel outcast, it's your duty to bring them in. If everyone around me is happy, I typically feel happy and fulfilled. So when I come into the world of education, I want to start off simple. Making sure the kids I work with are enjoying themselves. If every player is happy, the lessons will come naturally. If they are happy together, I believe that teamwork will naturally form. Stefan: You’ve worked in social work/healthcare, but you're somewhat of an outsider to the educational side of our mission. What has made an impression on you thus far? What unique vision do you hope to bring to game-based learning? Felix: I think that I am unique in my experience being on the other side of the program. My whole future became filled with more options because it opened up the possibility of having a different future than the one I thought I was unwillingly destined to follow. I want the kids I work with to realize that the things they experience in the game can be applied to real life. They can be so much more than the path they are expected to follow. If they enjoy helping people in the game I want to be able to turn that around and have them realize that they can have a job in the future where they help people. Stefan: Wow, you have no idea how suspiciously that ties into the theme of the article I’m writing. Thank you, Felix.

0 Comments

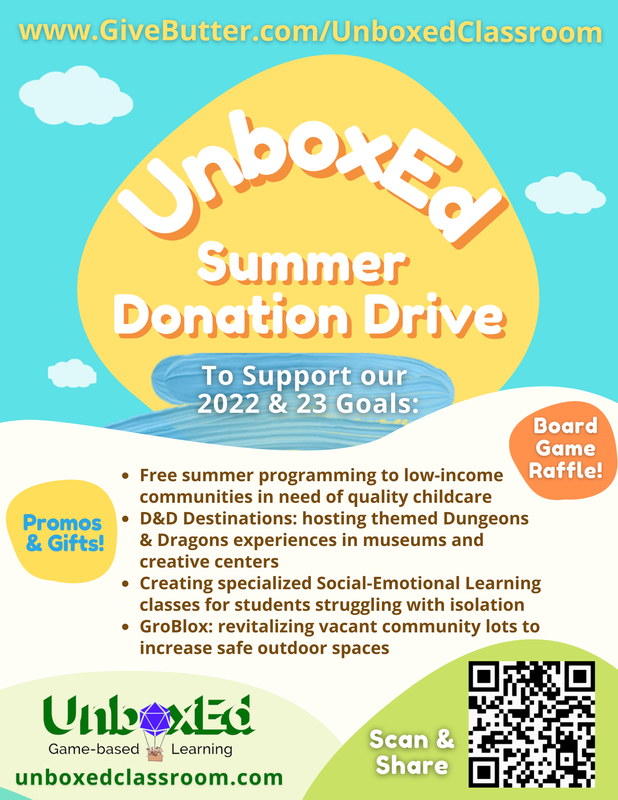

Most people probably think about literacy as the competency to read and write. For many educators, their first thought probably drums up SpEd interventions, breakthroughs, small group learning, particular students who have struggled or succeeded in their care: they see the trenches of the literacy battlefield. They know that illiteracy reduces the world to a fraction of its richness; they see the opportunities and light that open up for a child once they access a new form of communication. Literacy is possibly the humanization of a student. We want to speak about literacy in this larger context. We’ll start broad, as always, and shamelessly theoretical, and work our way down to what all of this has to do with games. (Spoiler: it mostly doesn’t.) All with the caveat -- and disclaimer -- that this one might get more spiritual than usual. One of the reasons UnboxEd chooses to operate in magical worlds, is the attempt to reflect the magic in our own. Is there a difference between magic actually existing, and living your life as if it does? Through this lens, we see literacy as synonymous with imagination, the measure of a student’s universe, the quality of opportunities and functioning within their community, and exploration of new cognitive and ideological pathways. Three examples come to mind when we broaden literacy. One from a RadioLab podcast on the Power of Words. The first time a new language emerged in recorded history happened in Guatemala in the late 70s. Children at the country’s first deaf school invented their own sign language. As generations of students passed through, expanding the language’s vocabulary over time, lingual studies found that 1) the current students, with access to a greater volume of words, had a far more developed cognitive, creative and emotional capacity than former students; and 2) as the younger generations socialized with former students at deaf recreation centers and taught them new words, the former students’ neural networks grew to match the younger generations. Greater access to words can literally open up new connections, ideas, and emotional understanding. Literacy expands your mind. Secondly, we recently learned that many scientific discoveries, especially in the realm of neuroscience and micro and cellular biology, were catalyzed simply by the means of a clearer picture. The advent of microscopes ushered in a flurry of scientific discoveries, as did the increased accuracy of medical illustrations. It seems almost silly, but the act of seeing things more clearly, in new dimensions, and with greater fidelity, sparked inspiration and more imaginative theories as to how those building blocks interacted beyond the page. Literacy is clarity. To bring it back to games, it lastly calls to mind an experiment that the goddess of game-based learning, Jane McGonigal, conducted over ten years ago and describes in her book, Imaginable. She created a simulation of a pandemic and for months participants played out choices within that crisis. The fruit of that study didn’t ripen until a decade later, when she found that the participants of that experience had suffered far less anxiety, stress and depression than the average citizen during this current pandemic. Literacy is schema. In the book Actual Minds, Possible Worlds (which we otherwise don’t recommend), Jerome Bruner describes how learning culture is created through the power of language. He studied the modals (bundles of words or phrases) that teachers used, and found that they correlated to a student’s perception of learning. Modals indicating a lack of confidence, or uncertainty, or disinterest, “might, could, maybe, sort of” transferred those same attitudes into students. While modals of passion, excitement and conviction created those same sensations in students. Here, the power of literacy wasn’t in transferring a concept as effectively as possible, but in inviting the student to step into the pleasure of passion, and extend their world of wonder and possibility. He labels this bridge created by language a “loan of consciousness,” (aligning and building on Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development), and describes his own obsessed, inspiring chemistry teacher not as a transmission device, but as a human event. Where all of this collided for us was the results of an innocuous warm-up we posed in our Entrepre-newbies class. One day we asked, “What is your dream job?” We assumed answers would come back reminiscent of our own childhood: doctor, teacher, artist, whatever amoebic business-thing our dads did. Instead, over 50% of the answers cited a job in the fast food industry. Another quarter referenced social media fame. One girl wrote “lawyer,” and added, “I wrote what I thought you wanted me to write.” That was eye-opening: our students’ vocabulary of opportunities consisted of either the world that immediately surrounded them, the world they escaped to, or the world they felt they looked in on from the outside. Not a world they freely imagined. When people think a goal is unobtainable, they are less motivated to work toward that goal. That’s not just common sense, it’s economical. It’s why a privileged childhood is full of platitudes of “putting your mind to something” and “dreaming big” and “shooting for the moon.” It becomes self-fulfilling. The important part is not the goal itself, but the language of achievement and possibility. Put more eloquently, Lisa Bu's rather boring TED talk ends with one of the most inspirational and rational messages we’ve ever heard: “Coming true is not only the purpose of a dream. It's most important purpose is to get us in touch with where dreams come from… even a shattered dream can do that for you.” Many people don’t have to practice dreaming. It’s similar to success, genius, or happiness in that way. Once we begin to “other” it, instead of seeing the hard work, struggle and cultivation behind it, we shelf it away as inaccessible. For some demographics, dreaming of something bigger is a literacy problem. We started Entrepre-newbies because we saw that, like struggling readers, many of our students, as well as their parents (and even our own colleagues), faced a similar effacement of ownership. They claimed economics was too complicated or might as well have been a foreign language. How many times have we all heard that about math? About logic and scientific principles? About therapy, analyzing literature, or social-emotional wellness? (Specific to SEL, we invite you to check out our appearance at the International Literacy Association’s panel on D&D for Social-Emotional Literacy.) Also, as for calling them “soft skills,” that’s dumb; let’s quit. Communication and interpersonal competence take hard work and practice. They are the concrete foundation on which learning, creativity and wellness are built. Empathy is literacy. Someone walking out of a car dealership or buying a home with a predatory loan is a literacy problem. Not understanding debt, credit cards, depreciation, loan interest, or the power of investing and compound interest, is a literacy problem. Beyond dreaming, beyond practical, beyond economical, literacy is the language of both negotiation and education. A literate mind can engage in fruitful debate; it can hold both a mind open to new information as well as a conviction. It can recognize and address dissonance, or discover the tool that can. When we think of education as a cultural, community and civil institution, we think of it as a forum: a stance open to counter-stance. (See also: Democratization of the Classroom.) The ability to inform one’s self begets a desire to be better informed. For those to whom literacy came easily, they don’t often think about the struggle it takes for others to arrive; and more likely, they also forget that there was no external force or system telling them that it didn’t belong to them. We had a student in our Entrepre-newbies class who had a learning disability. He barely graduated 5th grade. Within our group, he volunteered for a surprising responsibility, when the expansion of our fantasy business required one player to study chemical and electrical engineering at a university, in order to invent a magical battery. For two months, he stayed after school twice a week to attend college in a game world. He solved all the challenges we threw at him, graduated and invented a battery that opened up a hundred new possibilities for the business. The pride was beaming, but the cheers were cut short, because we had so many new ideas to pursue. We talked to the student after group that day, to congratulate him and ask if engineering was an actual interest of his; if he might study engineering in real life, given how proud it made him feel. “No,” he said, conclusively. “I’m not one of the smart kids.” So what’s the point? Why did us game folks spend a whole article talking about language? Did it do anything for that student above? Honestly, we don’t know. Game-based learning is not a silver bullet. SEL especially takes time. We can only hope he keeps absorbing wondrous language, and finding the right human events. Literacy has less to do with games as much as it has to do with our mission. There are two ways to think about the brain, its Pragmatic Mode and its Narrative Mode. Pragmatic mode is computational, functional, rational. It solves problems accurately and efficiently. It gets you an answer, but it will never operate in a way that makes 1+1 equal more than 2. Narrative mode is meandering, chaotic, not necessarily practical. But it can create meaning. It can create answers that equal more than their sum. It can imagine. It can dream. Essentially, it can lie to us. It can tell us awful stories that strip us of our agency; and it can tell us improbable stories that hold epiphanies we’ve never considered before, build fantasy worlds that create real heroes, expose fallacies that reveal hard truths, and dream of possibilities greater than our circumstances. Now that summer has officially arrived, we are proud to announce a new milestone for UnboxEd: due to demand, we are launching our first official fundraiser to meet all of our fall, spring and summer goals. The fundraiser is running June 22nd through July 20th and can be found here:

Our GiveButter donation page! We invite you to visit our donation page, hear more of our story, see what we’ve built during the last year and where we hope to go, and consider supporting us by donating or sharing the message with others. All proceeds from the drive will be used toward:

We've included the flyer for the donation drive to share on social media, or with anyone you feel may see the value of UnboxEd, as well as any local business that might be interested in sponsorship. Thank you for all of your support and faith thus far. It has been a banner year and we're excited to start dreaming even bigger. This Spring, we were honored to appear on the Mat & Board podcast to talk about our work using Narrative RPGs in the classroom. The episode features a conversation about the background of the program, the democratization of rules, evaluation and feedback systems, and games as powerful simulators.

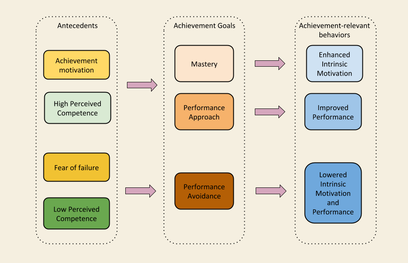

We also caught the attention of Wizards of the Coast (makers of D&D) who interviewed us in their official D&D Magazine! Hope you enjoy. Democratization of Rules The open discussion – and agreement – of rules, culture, and expectations makes one feel as if his or her voice and ideas are valuable. This reinforces a team mentality and an intrinsic motivation to fulfill one’s responsibilities within a group. Student Agency Research shows that students retain far more knowledge when they engage with content that interests them. So why not put them in the driver’s seat and let them discover how education best serves them, by giving them the freedom and the resources to explore their passions. Evolving Reward Systems Many disadvantaged students have few role models in their lives to demonstrate that education will lead to success. They require frequent and personalized feedback to pioneer their own model of success. Rewards should incentivize a student’s individual strengths instead of punishing their weaknesses. In the game world, this is known as “min/maxing.” Simple methods such as positive language and additive scoring (metrics that start from zero and count upward) provide students with frequent validation, reduce competitiveness, and give students a sense of tangible progress. Creative Problem-Solving Creativity opens up pathways to new forms of self-expression, empathy, and ways of relating to others. Creative thinkers value diverse ideas when approaching a challenge, but also have the confidence to defend their own. Risk-taking Often, the first step toward learning is failure. Any great accomplishment weathered a heap of failures. The goal is to eliminate the fear of failure. Risk-taking must be re-imagined as a necessity of creative problem-solving. Protecting students from failure results in an educational system designed for the lowest common denominator. We want students to fail often and fail better. In our view, wisdom does not come from experience; wisdom is earned from one’s response to experience. Curiosity and Skepticism Without skepticism, there is no science. Equally important to a student’s success is not only the knowledge to answer questions, but the delight in questioning answers. A healthy mistrust of information has never been more important. Communities need members who appreciate new information, but vigilant enough to debate its motives, rationality and reality. Combinatorial Innovation Huh? Basically, it means communities leveraging their networks. With how isolating technology can be, we can’t forget to support social innovation. So-called “soft skills” will become more important and sought out as the world grows more automated. Interacting – not transacting – with each other, exchanging ideas and skills, and creating warm communities will be invaluable. Finding opportunities to be human will become a creative task. |

SubscribeSign up to receive monthly emails, sharing research and insights into the world of game-based learning. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed