|

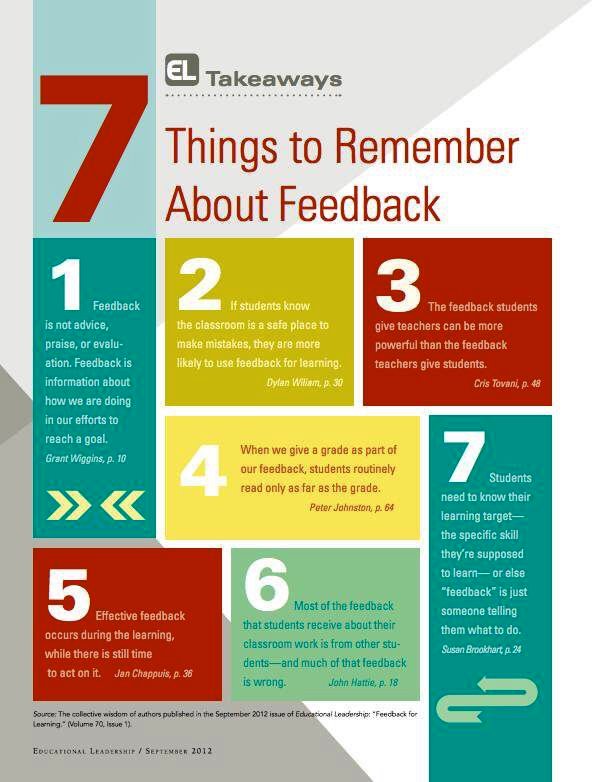

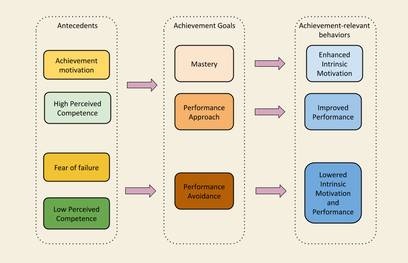

In the gaming industry, there is no shortage of definitions for “game” or “play.” This article isn’t overly concerned with the what, as much as asking why we play, and the various ways in which we’ve studied how we play. There is also no shortage of the studies of play. The American Psychological Association found that children who engaged in active play for 1 hour per day were better able to think creatively and multitask. Gamers also exhibited more emotional resilience during conflicts. Columbia University showed that physical play in 7- to 9-year-olds enhanced attentional inhibition (patience, focus and organization) and cognitive flexibility (the ability to grasp concepts more quickly as well as make connections and switch between concepts). As for why we play: essentially, play is practice. Given that play can be as abstracted, imaginative and social as we desire, play can better prepare us for nearly every realm of life. What gives play that power is the intention of meaningful discovery in a safe environment through the process of trial and error. The greatest benefit to play might be its attitude toward failure. So if play is inseparable from failure, and education is inseparable from play, shouldn’t failure be inseparable from education? Our experience tells us that students are far more likely to view failure as inseparable from finality. Meaningful Discovery The field of play is a field of discovery, and also catharsis. Rough, sporting, and competitive play enables people to safely explore multiple boundaries within the parameters of a game. Consequences are temporary. There is research linking the cessation of sporting activities during the pandemic with a rise in violence. Healthy conflict fosters communication, negotiation, fairness, and emotional regulation. It also stokes a curiosity for risk-taking (one of our Guiding Principles) while developing empathy as young minds learn the dual nature of harm. Another benefit it that play supports mental visualization. Make-believe. Through a series of experiments, researchers showed that students in small groups who explored a new concept before a lecture measured stronger comprehension than those who experienced the lecture before self-exploration. This has been reproduced in pre-schoolers better enumerating uses for an object pre vs. post instruction. Because they encountered more Productive Failure, thus iteration, students who began their learning without direct intervention developed more semantic knowledge and transference. Learning through play establishes personal connections of how and when to apply new concepts. Scaffolding Conversely, guided play, also called scaffolding, has supporting research as well. A famous researcher in the education world, Vygotsky, theorized that the most efficient learning occurs when a teacher is present to scaffold content in a way that resonates with and builds on top of a student’s prior experiences. Cambridge University used this concept in game-based learning to find that centering play around a defined goal, while allowing children to try various paths toward reaching that goal, did benefit their comprehension better than either self-exploration or direct instruction. For many of us, a “serve-and-return” form of play does begin from birth and follows us through much of our adolescence. Consider how much nonverbal communication and interaction transpires before a child learns to speak. Smiling, laughing, cooing, fear, discomfort and doubt can all lead to a reciprocal dance between child and parent. Social and Role Play Sociodramatic play is when children act out the roles of adulthood from having observed the behavior of adults. Studies suggest that this function of play is to build a prosocial brain that mimics effective peer interactions. Rats that were deprived of play as pups not only were less competent at navigating mazes later on, but their medial pre-frontal cortex was significantly less mature, suggesting that play deprivation actually stunts physical brain development. Rats with reduced access to play acted less socially and communally when they encountered other rats later in life. The concept of development and maturity is especially important, as some of the health effects of social play can’t be seen in the immediate or even medium term. A Berkeley study found that third-grade prosocial interaction correlated with those students’ eighth-grade reading and math outcomes better than with their third-grade reading and math outcomes. Fun: It Keeps You From Being a Grumpy Jerk Play and stress are also closely linked. Higher amounts of play are associated with lower levels of cortisol (stress chemicals). Play also activates norepinephrine, which facilitates synaptic connections and improves brain plasticity. The maturing of the pre-frontal cortex, as shown previously in lab rats, moderates the impulsiveness, emotionality, and aggression of the amygdala. Let’s translate all that. Taken place in a safe environment, play lowers stress, stimulates chemicals that help the brain learn, and during times of conflict and adversity provides a template for resilience, judgment and maturity against our primal impulses. Theoretically, play may be an effective therapy to an overactive amygdala, aggression, and uncontrolled emotions that result from childhood adversity, stress and trauma. This is likely why role play can be such a useful tool for developing empathy. To Screen or Not to Screen? Now that we’ve established so much goodness around play, a secondary topic emerges: video games versus in-person games. The bulk of studies in the gaming world center around video games, due to the fact that video game companies can and do pour a lot of money into research to defend and extol the benefits of gaming. Many reliable studies have found that video game players do show higher intellectual functioning, higher academic achievement, better peer relationships, and fewer mental health difficulties than non-gamers – though at this point, upwards of 75% of the population may fall into the casual gaming category. Parsing out the difference in quality between types of gaming is harder. One Berkeley study did compare traditional and digital toys, and found that traditional toys were associated with an increased quality and quantity of language development compared with electronic toys, particularly against solo electronic toys. In social pretend play, without the aid of a digital setting, children must collaborate on an environment and assign roles, which improves their ability to reason about hypothetical events. Digital media, if supported by scaffolding or co-play with peers, may have similar benefits, though the thinnest barrier between human-to-human interaction likely remains the best environment for learning. As humans are naturally communal, combinatorial innovation is far more likely to occur and spread through physical proximity. Good Failing and Bad Failing We spoke previously about the idea of Productive Failure and how it stoked creativity, problem solving and comprehension. The caveat to those findings is crucial: the consequences of failure cannot be perceived as too great, i.e. how most every student in the public education system perceives failing. Instead of creating an atmosphere where failure means trial and error, iteration, semantic connections and growth, failure has become a looming threat. This leads to performance avoidance, where instead of pursuing knowledge for its applications, interests or value, students perform only as well as sees them avoid punishment. They may never achieve a path to intrinsic motivation or independent learning, and may always rely on external incentives. In the world of game design, the only time a designer implements a system that subtracts is to introduce tension to the player experience. A timer counting down, running out of ammo, or losing all your money. This is the experience students encounter at school five days a week.

The value of grades and test scores holds their agency (another Guiding Principle) hostage. Supposedly, Google allows engineers to spend 20% of their office time on any project they desire, whether or not it’s related to work (though undoubtedly Google has a right to anything that is produced). As a result, productivity and retention are high, while upwards of 50% of their commercial projects come from employees pursuing an outside interest. Some schools have adopted this system by letting students study interests and hobbies unrelated to curriculum. Turning education back into play. They have shown reduced drop-out rates, improved behavior, boosted grades, and increased motivation. We are very interested in asking those students the original question, “How important is failure?”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

SubscribeSign up to receive monthly emails, sharing research and insights into the world of game-based learning. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed