|

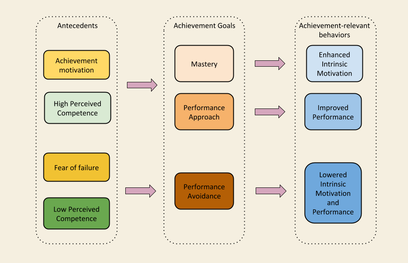

Most people probably think about literacy as the competency to read and write. For many educators, their first thought probably drums up SpEd interventions, breakthroughs, small group learning, particular students who have struggled or succeeded in their care: they see the trenches of the literacy battlefield. They know that illiteracy reduces the world to a fraction of its richness; they see the opportunities and light that open up for a child once they access a new form of communication. Literacy is possibly the humanization of a student. We want to speak about literacy in this larger context. We’ll start broad, as always, and shamelessly theoretical, and work our way down to what all of this has to do with games. (Spoiler: it mostly doesn’t.) All with the caveat -- and disclaimer -- that this one might get more spiritual than usual. One of the reasons UnboxEd chooses to operate in magical worlds, is the attempt to reflect the magic in our own. Is there a difference between magic actually existing, and living your life as if it does? Through this lens, we see literacy as synonymous with imagination, the measure of a student’s universe, the quality of opportunities and functioning within their community, and exploration of new cognitive and ideological pathways. Three examples come to mind when we broaden literacy. One from a RadioLab podcast on the Power of Words. The first time a new language emerged in recorded history happened in Guatemala in the late 70s. Children at the country’s first deaf school invented their own sign language. As generations of students passed through, expanding the language’s vocabulary over time, lingual studies found that 1) the current students, with access to a greater volume of words, had a far more developed cognitive, creative and emotional capacity than former students; and 2) as the younger generations socialized with former students at deaf recreation centers and taught them new words, the former students’ neural networks grew to match the younger generations. Greater access to words can literally open up new connections, ideas, and emotional understanding. Literacy expands your mind. Secondly, we recently learned that many scientific discoveries, especially in the realm of neuroscience and micro and cellular biology, were catalyzed simply by the means of a clearer picture. The advent of microscopes ushered in a flurry of scientific discoveries, as did the increased accuracy of medical illustrations. It seems almost silly, but the act of seeing things more clearly, in new dimensions, and with greater fidelity, sparked inspiration and more imaginative theories as to how those building blocks interacted beyond the page. Literacy is clarity. To bring it back to games, it lastly calls to mind an experiment that the goddess of game-based learning, Jane McGonigal, conducted over ten years ago and describes in her book, Imaginable. She created a simulation of a pandemic and for months participants played out choices within that crisis. The fruit of that study didn’t ripen until a decade later, when she found that the participants of that experience had suffered far less anxiety, stress and depression than the average citizen during this current pandemic. Literacy is schema. In the book Actual Minds, Possible Worlds (which we otherwise don’t recommend), Jerome Bruner describes how learning culture is created through the power of language. He studied the modals (bundles of words or phrases) that teachers used, and found that they correlated to a student’s perception of learning. Modals indicating a lack of confidence, or uncertainty, or disinterest, “might, could, maybe, sort of” transferred those same attitudes into students. While modals of passion, excitement and conviction created those same sensations in students. Here, the power of literacy wasn’t in transferring a concept as effectively as possible, but in inviting the student to step into the pleasure of passion, and extend their world of wonder and possibility. He labels this bridge created by language a “loan of consciousness,” (aligning and building on Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development), and describes his own obsessed, inspiring chemistry teacher not as a transmission device, but as a human event. Where all of this collided for us was the results of an innocuous warm-up we posed in our Entrepre-newbies class. One day we asked, “What is your dream job?” We assumed answers would come back reminiscent of our own childhood: doctor, teacher, artist, whatever amoebic business-thing our dads did. Instead, over 50% of the answers cited a job in the fast food industry. Another quarter referenced social media fame. One girl wrote “lawyer,” and added, “I wrote what I thought you wanted me to write.” That was eye-opening: our students’ vocabulary of opportunities consisted of either the world that immediately surrounded them, the world they escaped to, or the world they felt they looked in on from the outside. Not a world they freely imagined. When people think a goal is unobtainable, they are less motivated to work toward that goal. That’s not just common sense, it’s economical. It’s why a privileged childhood is full of platitudes of “putting your mind to something” and “dreaming big” and “shooting for the moon.” It becomes self-fulfilling. The important part is not the goal itself, but the language of achievement and possibility. Put more eloquently, Lisa Bu's rather boring TED talk ends with one of the most inspirational and rational messages we’ve ever heard: “Coming true is not only the purpose of a dream. It's most important purpose is to get us in touch with where dreams come from… even a shattered dream can do that for you.” Many people don’t have to practice dreaming. It’s similar to success, genius, or happiness in that way. Once we begin to “other” it, instead of seeing the hard work, struggle and cultivation behind it, we shelf it away as inaccessible. For some demographics, dreaming of something bigger is a literacy problem. We started Entrepre-newbies because we saw that, like struggling readers, many of our students, as well as their parents (and even our own colleagues), faced a similar effacement of ownership. They claimed economics was too complicated or might as well have been a foreign language. How many times have we all heard that about math? About logic and scientific principles? About therapy, analyzing literature, or social-emotional wellness? (Specific to SEL, we invite you to check out our appearance at the International Literacy Association’s panel on D&D for Social-Emotional Literacy.) Also, as for calling them “soft skills,” that’s dumb; let’s quit. Communication and interpersonal competence take hard work and practice. They are the concrete foundation on which learning, creativity and wellness are built. Empathy is literacy. Someone walking out of a car dealership or buying a home with a predatory loan is a literacy problem. Not understanding debt, credit cards, depreciation, loan interest, or the power of investing and compound interest, is a literacy problem. Beyond dreaming, beyond practical, beyond economical, literacy is the language of both negotiation and education. A literate mind can engage in fruitful debate; it can hold both a mind open to new information as well as a conviction. It can recognize and address dissonance, or discover the tool that can. When we think of education as a cultural, community and civil institution, we think of it as a forum: a stance open to counter-stance. (See also: Democratization of the Classroom.) The ability to inform one’s self begets a desire to be better informed. For those to whom literacy came easily, they don’t often think about the struggle it takes for others to arrive; and more likely, they also forget that there was no external force or system telling them that it didn’t belong to them. We had a student in our Entrepre-newbies class who had a learning disability. He barely graduated 5th grade. Within our group, he volunteered for a surprising responsibility, when the expansion of our fantasy business required one player to study chemical and electrical engineering at a university, in order to invent a magical battery. For two months, he stayed after school twice a week to attend college in a game world. He solved all the challenges we threw at him, graduated and invented a battery that opened up a hundred new possibilities for the business. The pride was beaming, but the cheers were cut short, because we had so many new ideas to pursue. We talked to the student after group that day, to congratulate him and ask if engineering was an actual interest of his; if he might study engineering in real life, given how proud it made him feel. “No,” he said, conclusively. “I’m not one of the smart kids.” So what’s the point? Why did us game folks spend a whole article talking about language? Did it do anything for that student above? Honestly, we don’t know. Game-based learning is not a silver bullet. SEL especially takes time. We can only hope he keeps absorbing wondrous language, and finding the right human events. Literacy has less to do with games as much as it has to do with our mission. There are two ways to think about the brain, its Pragmatic Mode and its Narrative Mode. Pragmatic mode is computational, functional, rational. It solves problems accurately and efficiently. It gets you an answer, but it will never operate in a way that makes 1+1 equal more than 2. Narrative mode is meandering, chaotic, not necessarily practical. But it can create meaning. It can create answers that equal more than their sum. It can imagine. It can dream. Essentially, it can lie to us. It can tell us awful stories that strip us of our agency; and it can tell us improbable stories that hold epiphanies we’ve never considered before, build fantasy worlds that create real heroes, expose fallacies that reveal hard truths, and dream of possibilities greater than our circumstances.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

SubscribeSign up to receive monthly emails, sharing research and insights into the world of game-based learning. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed