|

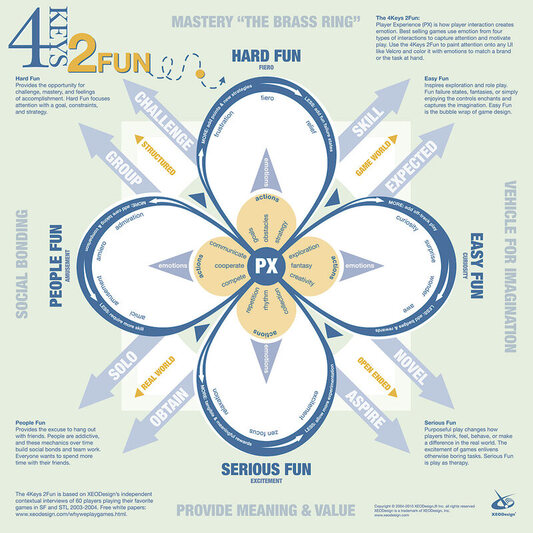

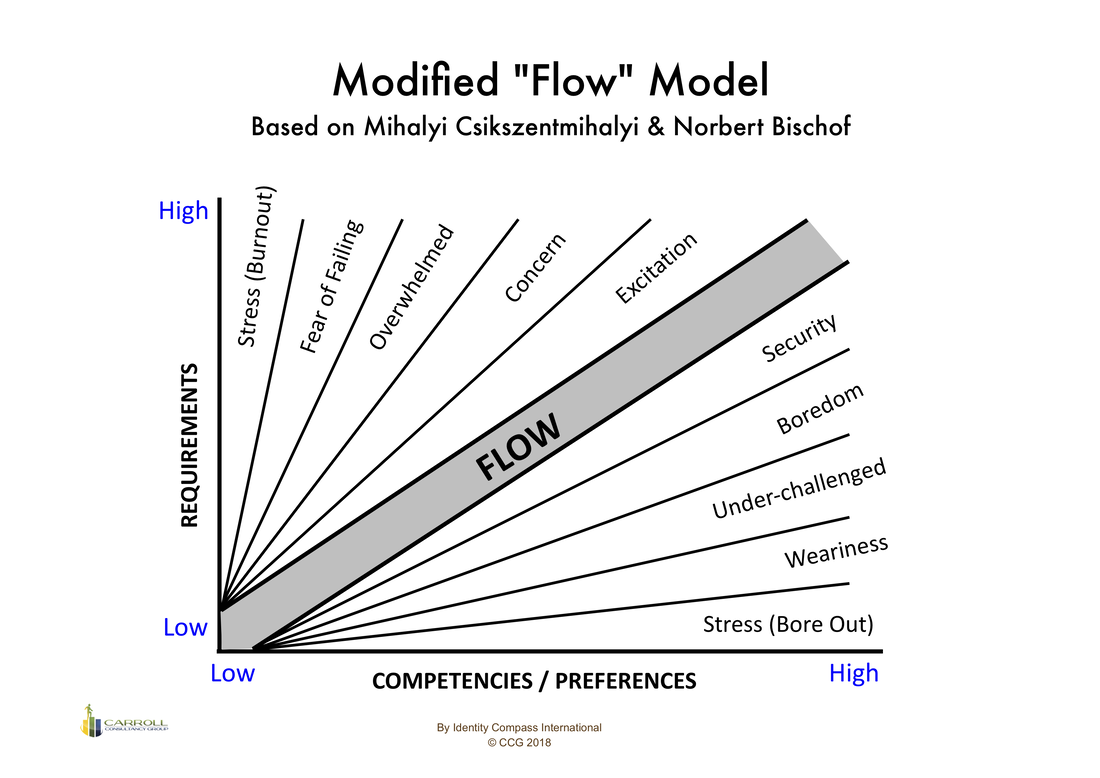

(AKA the one where you realize you might be more addicted to games than your kids) In an earlier blog post, we covered the myth that violent games create violent attitudes. Our previous article dealt with the myth that games inhibit productivity, as we discovered why so many young people turn to games not as an escape but as a source of self-efficacy. Today we want to discuss an important distinction within the gaming world: when and why games become addictive. We’ll introduce the different types and qualities of fun, what happens in our brains during those forms of stimulation, and how many popular games – and media -- have learned to manipulate just that. Nicole Lazzaro is a researcher who earned her success by theorizing the ‘4 types of fun’ almost 20 years ago. Her work has become canon for many game and UX (user experience) designers. Based on mapping the emotional responses of gamers, she bucketed fun into 4 categories: Fun of Novelty, People Fun, Fiero (Accomplishment), and Flow (Engagement). Novelty, also known as Easy Fun, is the surprise and delight commonly associated with simple, light games and activities. This is the fun that comes from stimulating our curiosity and creativity, allowing us to explore new worlds, engage in discovery, and invent. It’s the basis of role play and imagination, where we can experiment with identity and sampling new characteristics. The reward for Novelty is innovation. In a study of preschoolers who were asked to define the utility of a group of random objects, researchers compared children who studied the objects independently versus children who were first offered direction by an adult. The children who were allowed to engage with the objects through play named an average of 3 times as many nonstandard uses for the objects compared with children who were given a guided approach to the objects. This segues into the second realm of fun, Flow. This sort of fun is all about zen engagement and hyper-focus, and aligns with one of the foundational pillars of Self-Determination Theory, Agency, which we spoke of in depth in our prior article. Flow is the optimal blend of challenge and reward that players require to maintain a constant state of immersion. To achieve this, a game or activity needs to first succeed at offering the player visibility into all of his or her choices and abilities. Players must feel that they have the knowledge and skill to affect the world. This creates self-efficacy. Self-efficacy creates intrinsic motivation. However, games are also masterful sources of extrinsic motivation. Their feedback systems record and reward the history of a player’s past achievements, and constantly generate new tasks and new rewards designed to match the player’s growing abilities, all while offering the player immediate visibility as to how each of his or her decisions affects the environment; most specifically, reinforcing which actions will earn the player his or her next reward. This creates a constant state of progression and anticipation, which releases vast amounts of dopamine, a chemical in the brain that transmits feelings of pleasure and motivation.

If Flow is a dopamine drip, Fiero is a firehose. Fiero, Italian for “proud, fierce, and bold” is the type of fun that is intense, earned, scarce and explosive. Fiero is that underdog moment when against great odds, a player achieves an improbable victory and hurtles his arms in the air and shouts, “Finally!” Fiero is achievement fun, and requires that the Flow state be skewed toward the frustrating end of the spectrum. Fiero can’t be achieved without first dragging the player dangerously close to the point of rage-quitting. Fiero also fulfills another pillar of the Self-Determination Theory, Competency. Using the Flow model of progression, games and play are excellent facilitators of learning. We’ve previously spoken about distributed practice and knowledge checks; when added to powerful intrinsic and extrinsic motivators, games expand a player’s cognitive performance in ways that the educational system ought to be envious of. Not only does play activate norepinephrine, which activates alertness and improves brain plasticity, but higher amounts of play are correlated to lower levels of cortisol. Play reduces stress. Can it reduce anxiety too? Research does show that the neuroplasticity created through games allows players to apply their analytical and problem-solving competencies to everyday contexts, reducing their anxiety when encountering unfamiliar real-world situations. Anecdotally, we have worked with many Special Ed students and children on the autism spectrum who first escaped into games to combat their social anxieties, and wound up learning the communication, emotional and analytic skills that allow them to succeed in social situations. A great segue to the final mode of fun, People Fun. This is the general satisfaction of creating a brief, dynamic community with strangers or loved ones around a shared experience. Games stimulate all sorts of social emotions, including Schadenfreude (the enjoyment of another’s misfortune), Naches (the pride of seeing a peer succeed), teamwork, healthy competition, and sportsmanship. This completes the Self-Determination pillars, adding Relatedness. Just as in solo play, People Fun is the result of another neurotransmitter, the hormone oxytocin, which is a brain chemical associated with social bonding, trust and empathy. Even virtual games can stimulate oxytocin (though, have a listen to this podcast with Jamie Madigan where he discusses the psychology of online friends and how they fulfill about 80% of our social needs, but aren’t quite a full substitute for physical friendships.) That all sounds like a bunch of positives, so where’s the dark side? How does addiction manifest? By now we are all familiar with the corrupting potential of social media, not to mention drugs. Games rely on, and are designed to manipulate, the same chemicals that cause other addictions. Dopamine operates under the principle of tolerance. The more of it we release, the more of it we need to feel the same degree of pleasure. Many popular games literally turn this into an economy. To keep up their dopamine levels, players constantly feel compelled toward new rewards, new environments, new aesthetics, and new challenges. Some game companies make you pay for every inch of it. Loot boxes, weapon upgrades, avatar skins, sequels, prequels, supplemental Downloadable Content (DLCs). To maintain Flow and the progressive sense of validation, not to mention tangible rewards, players can become physically and mentally addicted to the anticipation and stimulation of new elements of the game, and pay continuously for it. What’s worse, is that at some point it stops registering as fun. While dopamine is associated with pleasure, it doesn’t automatically create positive emotions, as it’s equally aligned with motivation. That motivation can also produce stress, frustration, resentment and regret. Many players who are addicted to games as simple as Candy Crush and Farmville express negative emotions after continuously paying tens or hundreds of dollars to progress in the game. Oxytocin is another, more familiar culprit. When you see a new Like, tag, or message on social media, the feeling of joy comes from the same chemical as Social Fun, oxytocin. Oxytocin, like dopamine, requires higher and higher doses. The same research used in games and UX produced the addicting aspects of social media. The same research also designed touch screens to use the same intimate gestures we share with loved ones. Indeed, your brain registers the way you touch your phone as a signal of bonding. The same research, same principles, same input, same output, same manipulation. Might as well consider it all a game experience. Or rather, a gamed experience. When you’re wondering if your kids are addicted to games or media, teach them to ask themselves these questions. Then ask yourself the same. Do you reflexively open a game, website or app and realize you had closed it moments earlier? While using a particular game, website or app, do you feel: Energized, or empty? Joy, or stimulation? Excited, or compelled? When you close a particular game, website or app, how do you feel? While there are different forms of fun, born from different antecedents, as a whole, I’m not sure we draw an honest line between our expectations and our outcomes when it comes to small but daily interactions with media. One of our favorite aphorisms here is, "Practice like you play." If we may re-interpret it, a routine check-in with ourselves may be necessary to make sure that we stay present with the virtues of play. We suggest, "Practice why you play."

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

SubscribeSign up to receive monthly emails, sharing research and insights into the world of game-based learning. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed