|

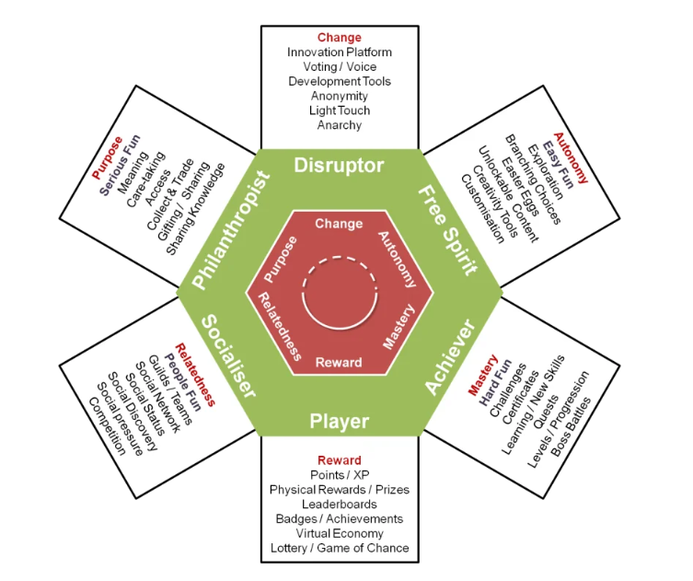

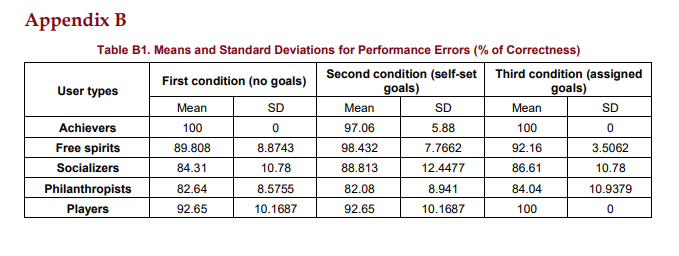

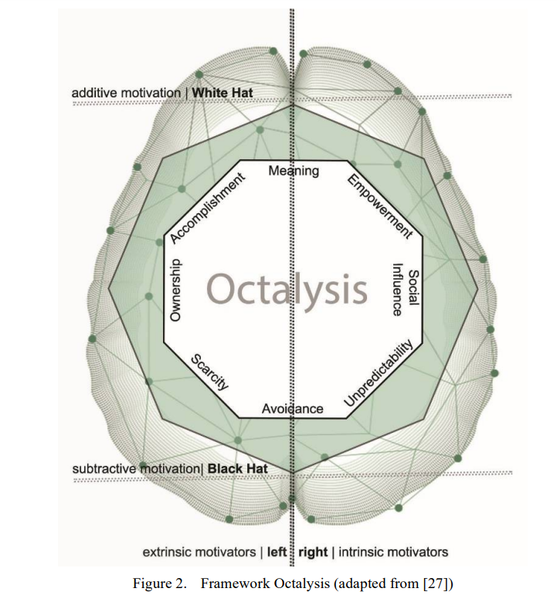

In education, one constant is the amount of assumptions that run up against a brick wall. Steven Levitt and Sendhil Mullainathan cover this topic in this podcast, distinguishing (though not defending) academics and researchers from the bulk of society who try everything they can to avoid admitting, “I don’t know.” Our most recent assumption that went up in flames was a foundational one: all kids love games. We’ve come to realize how complex of a statement this really is, and have since dived into a myriad of literature concerning Player Types (PT) and player motivations. Turns out, there are many overlaps with the previously-discussed Self-Determination Theory (SDT) framework, personality types, neuropsychology, and our beloved Agency. There a lot of different reasons why someone might enjoy playing a game, including in some cases the pleasure of ruining the game for others. This framework is useful for aligning an instructor’s approach to feedback, flexibility and engagement. We will be drawing largely on Marczewski’s Typology that studied gamification specifically, which drew on foundational research done by Bartle to produce the original Player Typology. We’ll describe what drives each PT, how they may fall to the dark side, and how one can redirect errant behaviors by understanding the underlying goals they are each seeking through their behavior. It’s important to remember, everyone is a mix of Player Types, with one type likely dominant. If you want to determine your own Player Type, you can take a quiz here. Marczewski’s HEXAD Socializers: Socializers are motivated by Relatedness, one of the tenets of SDT. Simply, they want to create social connections. They gravitate toward systems and mechanics that promote interaction, like NPCs, voting, coopetition, negotiating, and bluffing. Socializers are also perhaps the most nuanced PT, with new research citing that there are multiple subtypes that need more investigation. They are also the only type whose motivations and behaviors lie equally outside of the magic circle, interacting with and benefitting from the facilitation and organization of the real-world social setting. Philanthropists There can be a fine line between Socializers and Philanthropists, who are motivated by Purpose. Philanthropists want to feel as if they are part of something bigger, so will seek out interactive systems to achieve this, as their altruism desires to benefit other players with no expectation of personal gain. (We can recollect our moms falling into this category). Gifting, knowledge sharing, trading, community-building and sacrifice are mechanics that excite Philanthropists. This is also the type who takes the time to provide the bulk of answers on public forums, in order to help his or her gaming community. Free Spirits Free Spirits are motivated by autonomy (also part of SDT) and self-expression. They have at least two subtypes, Explorers and Creators. Explorers want as few restrictions to the width of the game as possible, and are the most likely to bump up against edge cases, find fiddly rules too restricting, propose a litany of house rules, and discover gaps in an imbalanced system. Creators want to build new things, draw and decorate their avatars, add personal content and design the world as often as possible. New research suggests a further subtyping, separating Free Spirits into those who seek Catharsis in games, or a means to escape from reality into tidier systems where they feel more freedom and efficacy; and Stimulation, or seeking excitement from the act of testing hypotheses, deduction, and assuming identities they otherwise wouldn’t have the opportunity to explore. Achievers Along with Philanthropists, Achievers are the easiest type to identify. They are motivated by mastery (or competency, as defined in SDT). They want to learn, improve, collect and seek out challenges. However, this may vary between an intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, so they may or may not brag about their accomplishments, but are likely to be hyper-competitive with themselves and possibly others in an effort to master the game. They are excited by systems that add to a game’s depth: skills, upgrades, status, and engine-building, or that add trophies and progressive feedback. Performance Taking a look at how Player Types intersect when it comes to performance during a game, we can see that, not surprisingly, Achievers dominate when it comes to no assigned goals (a feeling of competency is their main motivator) and assigned goals (winning to them is a signifier of mastery), though Achievers dip behind Free Spirits when it comes to self-assigned goals, as this is a Free Spirit’s bread and butter, and Achievers tended to choose the most difficult tasks of any type. Free Spirits performed well in each category, without specializing into mastery, and outperformed even Achievers when it came to setting their own goals, likely in the realm of creation and exploration. Since autonomy is at their core, monolithic goals like winning may actually de-incentivize them. Socializers and Philanthropists performed the most consistently, while lagging the other types in goal achievement, likely because 1) most games don’t offer purely social or philanthropic mechanics, thus limiting their ability to access their favored win conditions and 2) accomplishments and endgame status are not a primary motivator. Another interpretation is that some Socializers and Philanthropists may be naturally less competitive, or resort to social connection as a way to defer from effort, a fear of losing, or insecurity about their competency. It seems that in games, nice guys do finish last, unless they decide that success means being a nice guy. Jekyll and Hyde As mentioned previously, there are dark sides to each of the types. Some are blunt, like Griefers and Destroyers. Others, like Improvers and Influencers, can ride the line of bane or virtue. Influencers will try to change the way a system works by exerting influence over other users. In cooperative games they are known as Quarterbacks. This is not inherently negative. If they feel the system is broken and you allow them a voice to discuss changes, they can become allies and advocates. Make use of them or lose them – worse still, they could end up switching to a Griefer. Griefers (this is the Killer in Bartle’s taxonomy) are direct disruptors, in and out of the game. They want to negatively affect other users, just because they can. It may be to prove a point about the fact that they don’t like the game, don’t want to be in the learning setting, are having a bad day, or feel insecure about their competency within the game systems; or it may be that they have learned to accept negative attention as favorable to no attention. Destroyers want to break systems within the game. This may be by hacking or finding loopholes in the rules that allow them to ruin the experience for others. Their reasons again may be because they dislike the game or it may be a deviant form of exploration or mastery, hacking things or besting opponents by any means. Adding constructive feedback and scaffolding can hopefully guide them toward being an Improver. Improvers will interact with systems with the best intentions in mind. They may find loopholes or make up rules that make more sense to them, but their aim is to change the system for the better. They are similar to the Free Spirit type, in that they want the autonomy to explore the system, identify problems and fix them. With care, they can be great leaders; ignored or mistreated, and they could retreat toward a Destroyer. The trick for every PT is to identify their internal motivators and gradually convert them from being impulsively reward-seeking into setting personal goals that are harmonious with the objectives of the learning setting, if not the game. Charting a Path Toward Intrinsic Motivation We’ve spoken at length about the complexities of intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation, and how games are superb at reinforcing self-efficacy. But as an instructor, part of the job is to make students aware of their own motivators and give them the tools to create their own sense of engagement. One simple source is empowerment. People tend not to enjoy things they’re bad at. Playing to a student’s strengths can make the difference between their light and dark sides, even if it means skewing systems to benefit the way in which a struggling student wants to play the game. Asymmetrical games or contrived asymmetry (tacitly giving one student improved abilities or equipment) can make players feel special, empowered, or give them the proper scaffolding to compete with more advanced players. Another source of engagement is meaning. We mentioned asymmetry, but another facet of balance is that players need to feel that their choices have influence over their outcome in the game. This is called self-efficacy or meaning-making. It’s what connects players to the magic circle, their avatar, the narrative arc and the social dynamics of a group. If it’s not apparent, accessible and rewarding within the game, Griefers and Destroyers can often spot an easy path to self-efficacy by ruining the game for others. Some methods to improve meaning don’t even have to be inside the game. Assigning one player as a Captain or Leader, a Rule’s Sherriff, a Treasurer, a Cartographer, etc. can give them a sense of purpose and value, as well as incentivize them to become a role model or abide by the game’s rules to maintain their status. Jobs can apply in the game as well, using roles that would apply to a mission, phase or achievement in the game. Counter-intuitively, cooperative games aren’t always the best choice for game-based learning (until you know your players well and have established mutual trust). This is because Griefers and Destroyers can wreak havoc on a cooperative game. In competitive games, at least the game’s systems can fulfill some of their negative intentions. But if everyone’s fun is hinged on them agreeing to play cooperatively, they may see this as an easy opportunity to wield their displeasure over the rest of the group. Splitting the players into competing teams may give disruptors a sense of allegiance and relatedness, as well as lowering the stakes so that they don’t feel as if they are solely responsible for their failure. It’s also a good idea to start off gaming sessions by reminding students that there is no penalty for losing or making bad decisions. Everyone is going to make mistakes; the point of games is iteration. School has given most students a phobia of failure. Try to undo that a bit at a time by lowering the consequences of experimentation – who says you even need to keep track of score accurately? Or consider supplementing scoring with individual inspiration points, meta currency or rewards toward a mega game. Physical rewards work wonders. Kids love nothing more than possessing something. Creating real-world trinkets, drawings, maps, figurines, cards, treasures and souvenirs that bring the game to life spark so much joy, and give them a tangible and emotional connection to positive outcomes. This is a perfect example showing that the best form of teaching is creating experiences. Combined with upgrades, skills, unlocks, discoveries, etc. these all provide demonstrable evidence of progress. Progress = competency = empowerment = engagement = curiosity = discovery = repeat. One thing to keep in mind: rewards, empowerment, and meaning should all be focused around the core loop of the system you are trying to teach. The act of a student demonstrating comprehension of a core learning objective should ALWAYS result in a pleasurable experience. That’s what games are most beautiful at: attaching intense, memorable, visceral feelings to great choices. For specific Player Types, let’s take a look at additive vs. subtractive motivators, and left brain (logic and analyzation) vs. right brain (creativity and socialization) motivators. For Free Spirits, Socializers, Improvers and Influencers, try to offer them less regulation and let them discover their own paths and rules. They thrive on anticipation, not results. Feed them unpredictable game states, randomness, social influence, an amplified voice, and opportunities for teamwork or treachery.

With Achievers, Griefers, and Destroyers, make them feel special. Scarcity, tasks, and personalization can be one way to help them appreciate a personal goal or reward. Invent trophies, rare items they can possess, and special missions. Just as in real-world economics, something is far more valuable when it is one-of-a-kind. As a post-mortem of this article, a colleague asked if this analysis applied to non-gamified learning, as well as adult learners. We can assume that most elements can be applied to any interactive learning setting, and any stage of development. Though separate research tells us that older learners gain more from repetition, whereas younger learners gain more from social proximity and the quality of direct and immediate feedback. Anecdotally, many of us can probably safely classify our moms as Philanthropists during childhood games. As for how well this typology extends to other realms of learning, we say: be the experiment you want to see in the world.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

SubscribeSign up to receive monthly emails, sharing research and insights into the world of game-based learning. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed