|

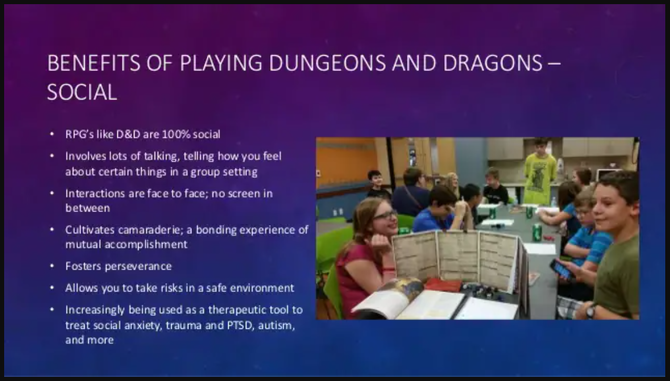

As we defined in our last post our assertion that school is a poorly-designed game, today we’ll compare the education system to a well-designed game, Dungeons & Dragons, and how we’ve seen students respond in the 5 years of using similar RPGs in the classroom. If you think the same quantifiable progress can’t be made through games, remember that games are almost purely made out of both quantifiable systems and systems of progress. Our students’ reading test scores improved dramatically, specifically their ability to identify relevant information from a passage. This comes from scouring a rulebook for specific information about their character, feats, weapons, rules, etc. Their ability to chunk texts and recreate a narrative in their own words improved as well. This was due to their interaction with so many nuanced characters and plot cues, foreshadowing, and having to make inferences about the game's story based on subtle clues and conversations. Basic math skills improved, including probability and deductive reasoning, less to do with equations and more to do with comparisons and decision-making. Also embedded in game math is a basic understanding of economics, value versus worth, resource management and distribution. Social problem solving increased. We wrote in the last article how failure is abstracted in schools. In narrative RPGs, problems are abstracted but failure is clearly defined, though not finite. Players immediately knew what they did wrong, which approach didn’t work, and became less afraid to make mistakes, since mistakes weren’t punitive. They result in a denial of progress, but nothing is lost. Mistakes require iteration. There is no penalty for solving a problem incorrectly, either once or ten times. Because of this students were introduced to the concept of alternating skills to find the one that worked best per situation. This also promoted cooperation between students. Their negotiation of strengths and weaknesses within the group was a refreshing departure from their binary labels of "high” or “low" students. As their individual character strengths grew, each student became identified by those strengths and depended on teammates to make up for their weaknesses. Another theory for their advancement with social problem solving is that the visibility and stressors of their normal lives and of the real world were absent in the game, or metaphorical, removing some of the intimidation in trying to solve them. Jamie Madigan, on The Psychology of Video Games, has a great episode about a group of therapists who use D&D with their patients by creating campaign scenarios relevant to the patients’ real world struggles, but abstracted in a safer game environment. In what eventually became the impetus for founding UnboxEd, in our 5th year we first experimented with using D&D to start a business with our students. Having economics and investing backgrounds, we made sure that the kids didn't get away with anything they didn't earn. Using the D20 System, modified character stats and our own experiences in commerce, we built a weekly P&L statement that covered payroll, property and corporate taxes, third party consultants, talent recruitment, supply chains, employee equity, ticket sales, concessions, promotions, marketing, litigation and on and on.

Halfway through the campaign, the growth of the business depended on the kids figuring out a way to invent the radio. The biggest challenge was how to power the device with no electricity existing within the world. One of the students in the group was in danger of failing fifth grade, and was in the at-risk category of dropping out before graduating high school. But he had an idea. For an entire year, he chose to stay an hour after school, twice a week, to attend college within our game, to learn chemical and electrical engineering, so he could invent a magical battery to power our radio. He ended up passing 5th grade. We were lucky enough to reconnect with those students recently, and he’s on track to graduate high school. We asked him during that year if he wanted to be an engineer in real life. He said, "No. I’m not one of the smart kids." Hating school doesn't mean hating learning any more than hating dodgeball means hating sports. I fail to see how his achievement in the game was different than a real-life outcome. It took discipline, persistence, luck, guidance, and time. The real difference is that the school he went to in the game was the version of learning that he wanted to see. The version he agreed to. Instead of an evaluation system that told him over and over that he wasn’t capable of what other kids were, he started with nothing and began to climb. He made all of the choices himself, and he recognized all of the obstacles ahead of him, that there were no guarantees, and while there were plenty of efforts that didn’t work, there was nothing in the system that told him he couldn’t succeed.

0 Comments

There are plenty of rumors surrounding why our educational system is designed the way that it is, plenty of conflicting ideas on how to fix it, and plenty of past solutions that are now part of the blame for its current quagmire. Strangely enough, when UnboxEd was in development and we began to compare our ideals with the design of public schools, we realized that our educational system can actually fall under the definition of a game.

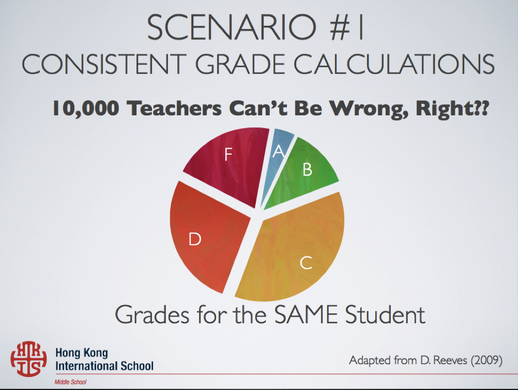

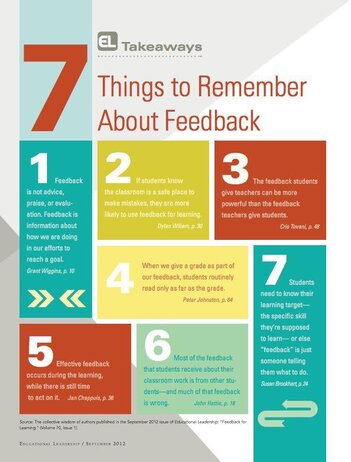

Let’s elaborate on each. Beyond the simplest function of making a game "work," what do rules serve? Rules shape the interactivity of elements in a game world. We often find stricter rule sets in linear games (players progress on a single ‘golden’ path, with transparent goals), while open, explorative games allow players more agency in their interaction, often using the player’s biases and assumptions as part of the puzzle that they must overcome. School falls under the linear, narrow campaign. Little, if any, of its systems are designed to respond to student agency. Rather, success often depends on students who are built for its demands. It’s a shame that we’ve gotten to a point, with a concept like education that we consider so exploratory, that not even the educators themselves have control or consent over the systems of education. So what is lost in that model? Being part of the rules process means you are invested in the system as a stakeholder and constituent. You have ownership over your world, and feel responsibility to abide by the rules you helped create. Skin in the game creates an incentive to preserve its integrity. Scoring, however, is our biggest gripe with public education. Grades cap achievement at 100, and count down commensurate with a student's errors. As a game designer, the only time we include a mechanism which counts down, be it a timer or health gauge, is when our aim is to introduce tension and pressure to the player experience. That's what grades do to students. This scoring system evaluates a narrow set of skills, mainly raw intelligence and memory, with some compensation for work ethic. It also ensures that all students are directly compared to one another on these few, specific skills without taking into account character or creativity. Students are labeled as "high performing", "low performing", or "average". They carry this mono-identity with them throughout their learning universe. They have no choice but to internalize it. "I am a [performance status] student". This system does not measure growth, it measures decay. Take a well-designed game as a comparator. Dungeons & Dragons begins every character at level zero and counts up as they progress, to a limitless number. Notice a difference in the language itself. You “gain” levels, “increase” experience points, “acquire” abilities, skills, feats, currency, and items. Failure is not punitive: it simply shifts the problem to a different set of trials. If A didn’t work, you try B. Players recognize the freedom to experiment with various paths, which incentivizes and rewards imagination and iteration. Each character has a unique path to achieving unique goals, solutions and growth. Instead of comparing one’s self to another student’s abilities and achievements, each student can identify as an inclusive sum of both strengths and weaknesses. Through the game universe, players constantly call, "I’m good at [ability], but I can't [skill] yet." Answered with, "No problem, I’ve got [skill]. Can anyone [ability]?" Think of game states as phases, arrived at through current factors and conditions. I want to focus on the Fail State. There is one major problem with the Fail State at school. It is binary and therefore abstracted from a goal as broad as cognitive growth. Pass or Fail. Those are the options. Which means students are not attempting to learn the material, they are attempting to achieve a Passing State. There's a big difference.

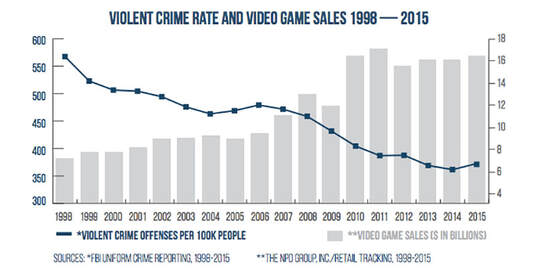

Without any nuance beyond Pass or Fail, students often don't care what they achieved, only IF they achieved the desired state. As educators, we consider the student having mastered or not mastered the material, mark the grade and move on to the next unit. The machine grinds on. Students don't experience a consequence until the next time a cumulative concept builds on top of the previously unmastered material, and they fall farther behind. If a student were to guess at each exam without understanding the material and luckily scored excellent grades, they would absolutely consider that a success. But would a parent or teacher consider that a success? Then who are our students learning for? Grades have been divorced from the premise of learning. The Pass/Fail State in school reduces achievement to a reactive, quantifiable chore, versus what could be a rich, meaningful action that demonstrates achievement. The current design teaches students to care more about achieving a high score than about learning, which makes cheating a profitable and sometimes smartest choice, under the lens of optimizing the game we've put in from of them. Good designers don’t blame players for breaking their game. They consider it poor design and fix it. We recently had a teacher email us to ask about incorporating D&D into the classroom. He had reservations, however, about introducing young students to a game about killing monsters and exerting aggression, and how to sell that to parents. Our response became more comprehensive than we expected, and we feel it's worth sharing. “I want to start by addressing a few assumptions, the first being that violence or aggression within play is inherently bad and should be suppressed. Part of the reason I started my first D&D club was that our school district had made it tough for young boys to appropriately express aggression and competitiveness. At recess, we had a policy to ban all rough or aggressive play and imaginary weapons of any sort. Similarly, in Art class there was a rule about ‘no blood, weapons or fighting.’ I personally support the research that demonstrates acts of aggression and competitiveness in play is not at all the same as BEING a violent individual. Heck, there's even a book on it called Killing Monsters. The research on violent games suggests that what creates violent attitudes is actually frustrating difficulty curves, not the content. Moreover, young boys use rough play to define the appropriate boundaries of aggression and competitiveness. For any child, not just boys, killing a monster provides 1) elements of teamwork; 2) immediate and direct validation of their developed skills, strategies and immersion in the game; and 3) a safe way to learn about caution, planning, morality and consequence/permanence. I think it's confusing for kids to be told that their instincts and impulses are ‘inappropriate’ or ‘wrong’ (remind anyone of Abstinence Education?), as opposed to helping them navigate the boundaries of those impulses and learn the rules for when aggression affects the rights and comfort of another person. I saw our club as an opportunity to help students confront some of these controversial subjects in their own language and on their own terms. However, I completely understand that this is a tough thing to talk to parents about. There are cultural and ethical differences between households. There are equally valid opinions on the matter. So I would encourage anyone to do their own research on the area of violence in games and share that information in hopes of calling out outdated science on the subject. The Psychology of Video Games podcast is a great starting place for many direct insights and references. Having said all that, my cheeky answer would be: recruit as many girls as possible into the group. I loved having girls in the party because they were far more empathetic, superior planners, and offered the game a richness that had nothing to do with monsters or fighting. They added a very real and very cool social aspect to the game. My final recommendation would be to ask the kids what they want the game to be. They might have the same assumptions that D&D is only about killing monsters, when that is such a small part of what the game can be. The most fun and rewarding campaign I've ever played with anyone of any age is our Entrepreneurship groups that we guide through building a startup business. For an entire year we aim our imagination at making a business thrive, without rolling a single combat dice, and the kids love every minute of it.

So the second assumption to bust is, you ain't gotta kill monsters. D&D can be a tabletop Minecraft. Maybe your kids want to build a city. Maybe they want to solve a mystery. Maybe they want to re-enact a situation in history that they are studying. If the intention is for the game to engage their curiosity, start by asking them, "what do you want to play today?" That's the long version of our response. Without venturing too close to Fight Club territory, we do feel there ought to be a degree of protection and privacy over student-led D&D campaigns. The integrity of the magic circle is something we take seriously. We trust our students to either act maturely or learn from their immaturity, and they trust us to keep our game a safe place where they are allowed to invent, experiment, test boundaries, be themselves and regulate themselves. The first job of a game master is to listen. A teacher's job is to illuminate a pathway. To deny kids opportunities of identity-creation because of our own assumptions about what's best for them is lecturing, not education. This Spring, we were honored to appear on the Mat & Board podcast to talk about our work using Narrative RPGs in the classroom. The episode features a conversation about the background of the program, the democratization of rules, evaluation and feedback systems, and games as powerful simulators.

We also caught the attention of Wizards of the Coast (makers of D&D) who interviewed us in their official D&D Magazine! Hope you enjoy. Democratization of Rules The open discussion – and agreement – of rules, culture, and expectations makes one feel as if his or her voice and ideas are valuable. This reinforces a team mentality and an intrinsic motivation to fulfill one’s responsibilities within a group. Student Agency Research shows that students retain far more knowledge when they engage with content that interests them. So why not put them in the driver’s seat and let them discover how education best serves them, by giving them the freedom and the resources to explore their passions. Evolving Reward Systems Many disadvantaged students have few role models in their lives to demonstrate that education will lead to success. They require frequent and personalized feedback to pioneer their own model of success. Rewards should incentivize a student’s individual strengths instead of punishing their weaknesses. In the game world, this is known as “min/maxing.” Simple methods such as positive language and additive scoring (metrics that start from zero and count upward) provide students with frequent validation, reduce competitiveness, and give students a sense of tangible progress. Creative Problem-Solving Creativity opens up pathways to new forms of self-expression, empathy, and ways of relating to others. Creative thinkers value diverse ideas when approaching a challenge, but also have the confidence to defend their own. Risk-taking Often, the first step toward learning is failure. Any great accomplishment weathered a heap of failures. The goal is to eliminate the fear of failure. Risk-taking must be re-imagined as a necessity of creative problem-solving. Protecting students from failure results in an educational system designed for the lowest common denominator. We want students to fail often and fail better. In our view, wisdom does not come from experience; wisdom is earned from one’s response to experience. Curiosity and Skepticism Without skepticism, there is no science. Equally important to a student’s success is not only the knowledge to answer questions, but the delight in questioning answers. A healthy mistrust of information has never been more important. Communities need members who appreciate new information, but vigilant enough to debate its motives, rationality and reality. Combinatorial Innovation Huh? Basically, it means communities leveraging their networks. With how isolating technology can be, we can’t forget to support social innovation. So-called “soft skills” will become more important and sought out as the world grows more automated. Interacting – not transacting – with each other, exchanging ideas and skills, and creating warm communities will be invaluable. Finding opportunities to be human will become a creative task. |

SubscribeSign up to receive monthly emails, sharing research and insights into the world of game-based learning. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed